Soka University welcomes mental health experts to discuss “Suicide: A Conversation. Real Insight. Real Hope. Real Help.”

The “Critical Conversations @Soka” series is a program at Soka University of America that focuses on igniting conversations, connecting the community and offering actionable information to positively transform pressing local and global issues.

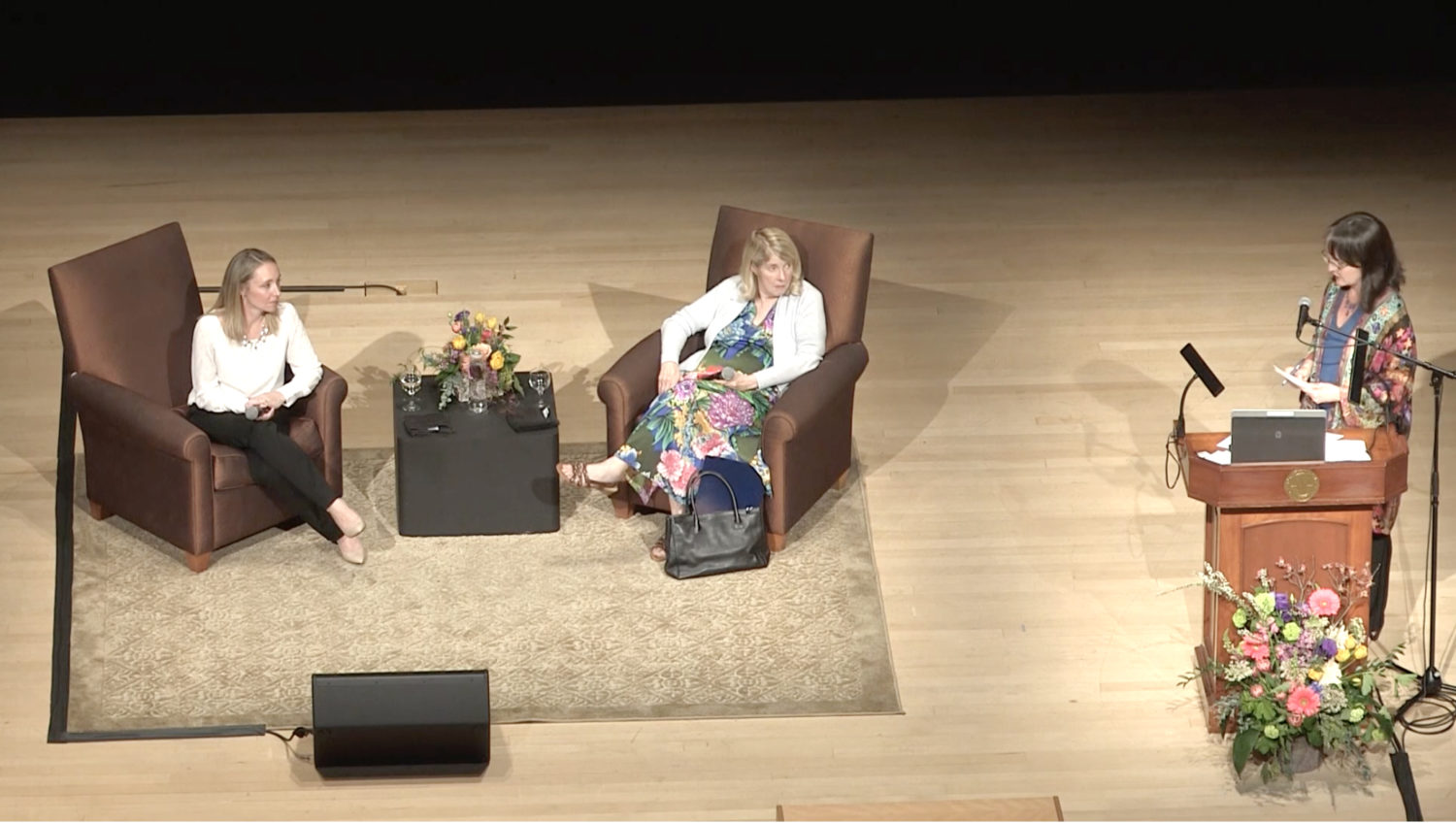

On April 16, Critical Conversations hosted “Suicide: A Conversation. Real Insight. Real Hope. Real Help.” The event welcomed mental health experts Alison Malmon, of Active Minds, and Dr. Kay Redfield Jamison, of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Offering their personal and professional insights, the speakers lifted up the conversation about mental health to create hope and prevent future tragedies.

“There Is Indeed So Much Reason to Have Hope.”

Alison Malmon was a freshman in college when she lost her brother and role model, Brian, to suicide, at 22 years old. People knew him as an outgoing, popular, smart student at Columbia University, but he had concealed his symptoms of depression and psychosis.

After Brian’s death, Ms. Malmon established a group at the University of Pennsylvania to give students a platform to discuss the oft-stigmatized issues of depression and suicide.

It was by sharing her own story that she realized “there was a generation that was desperately wanting to know more, to do more, to treat mental health as their social justice issue.”

Today, her group has developed into the national nonprofit organization Active Minds, which reaches nearly 600,000 students on more than 600 campuses annually.

The group’s mission is to change the conversation about mental health by first having a conversation—in schools, in communities and among peers.

Ms. Malmon concluded by urging those in attendance to take part in creating a space where mental health issues are talked about more openly, because “there is indeed so much reason to have hope.”

During a question-and-answer session, Ms. Malmon addressed the issue of helping others who resist support:

Keep letting them know that you’re there for them: “I’m here for you. I’m not going to judge you. I care about you.” And as a caregiver, you also deserve support. I would encourage you to talk to somebody, whether it be a therapist, parent or another friend, so that you’re not bottling up [feelings] inside.

When asked at what age we should start talking about mental health issues with young people, Ms. Malmon suggested very early on:

We need to be talking to kindergarteners about feeling sad and having bad days, and preschoolers about bullying. We need to use the words depression, bipolar disorder and suicide for high school students. Kids need to be given a vehicle to express their emotions. As a parent, when you’re having a bad day, be open about that and let your kids know. Then, when we get to a stage where we’re talking about mental illness, it’s not a brand-new thing.

“Be Proactive in Discussions.”

Named “Hero of Medicine” by TIME for her insight into mental illness, Dr. Kay Redfield Jamison, a professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, discerns the importance of not just talking about mental health issues, but doing so in an informed way.

She explains that while the issue is complicated, four to five major psychiatric illnesses involved in 90–95 percent of suicides are treatable. “It’s a question of getting diagnosed properly and treated correctly,” Dr. Jamison said.

In 1995, Dr. Jamison published the memoir An Unquiet Mind, now a best-seller. In it, she details her own struggles with bipolar disorder, which began when she was 17, culminating in a near-death overdose of lithium at 28.

Although she had been accurately diagnosed, she was constantly on and off her medication. Her brush with death was a wake-up call not to take her treatment lightly. She’s since responded well to medication.

Dr. Jamison then shared some sobering facts:

• Every 40 seconds, someone in the world takes their own life.

• In the U.S., suicide is the second leading cause of death for people ages 10–34.

• Mental illnesses hit early in life around 18–27, and the risk of suicide is highest in its beginning stages because of the difficulty of distinguishing between normal and mental turmoil.

But Dr. Jamison assured the audience that, even though it may seem hopeless at times, there are many treatments out there that work. “We know a lot about the underlying science, and the research is going very quickly,” she said.

Another important factor is teaching kids, parents and teachers about the symptoms of depression. “Education goes a long way,” Dr. Jamison emphasized. “Be proactive in discussions.”

For information about attending or streaming future “Critical Conversations @Soka,” contact Mary Kavanaugh at mkavanaugh@soka.edu.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles