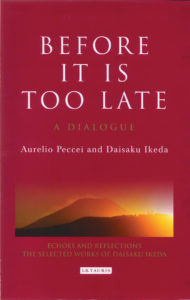

Ikeda Sensei and Aurelio Peccei met for the first time in Paris in May 1975. Over the next nine years, they met five times and kept in touch through correspondence. Shortly after Dr. Peccei’s passing in March 1984, their dialogues were published under the title Before it is Too Late. Below are excerpts from their dialogue, touching on the importance of human revolution to counter the crises that humanity faces.

Changing the Human Heart

Daisaku Ikeda: The grave world situation has led you to call for a humanistic revolution. Basing my thought on Buddhist teachings, I call for a human revolution, which is a way to change the inner nature of each human being and in this way bring about improvements in society as a whole. Through developed scientific technology, human beings in industrialized nations have created a way of life so materially rich that kings and aristocracies of the ancient and medieval past might well envy them. But man has used the same sophisticated technology to produce weapons of unprecedented destructiveness, weapons that have already taken a heavy toll in injuries and lost lives. Pursuit of material well-being has robbed man of the value and warmth of human exchanges. Instead of employing the immense power of science for the happiness and enhanced dignity of all humankind, a limited number of people and groups uses it selfishly to satisfy their own desires or in competition with each other to ascertain their superiority over each other.

Buddhism refers to the mental states behind such misuse of scientific power as the three poisons: greed, anger and foolishness, which Buddhist practice is designed to enable people to control. In primitive societies, taboos and punishments for their violation are established, and fear of retribution partly controls human misbehavior. In more advanced societies, reason is supposed to play a similar role. But for all humankind since its inception, many deep mental attitudes and operations lie beyond the control of reason. To deal with these attitudes and operations, Buddhism insists on faith and practice, and on a revolution at the deepest level of life, beyond the realm of reason, and the consequent development of powerful wisdom. My idea of the human revolution is based on this approach.

What kind of practical action do you propose for the attainment of what you call the human revolution? Do you have a religion or religious faith in mind?

Aurelio Peccei: When I affirm the need, and call, for a human revolution, I do not refer to any religious faith; as you know, I have in mind a profound cultural evolution inspired by a new humanism capable of illuminating and inspiring our generations in this materialistically oriented technological age. My discussion with you has nevertheless shown that, though you are guided by your Buddhist faith and though we start from different viewpoints and use different forms of expression, we are both talking about the same kind of change in the human heart.

What I maintain is that we all need to correct fundamentally our vision of ourselves, our world and our place in it, and hence of our way of thinking and mode of behaving. For quite a while now we have been acting under the overwhelming influence of the material revolutions, which have permitted us easily to impose our yoke and our whims globally at will, thereby strengthening our inherent belief in the absolute primacy of our species and favoring our opinionated concept as to our imperial nature. We have thus become dangerously self-centered and quite self-righteous and altogether so psychologically imbalanced that we have lost every possibility of making any serious critical analysis of our true condition and behavior. I have explained that, in my view, this is the main cause of our predicament.

To liberate ourselves from this fatal handicap so that we can make an overall evaluation of what has happened, or may be happening, to us and to undertake at the same time an objective selfanalysis to discover our faults and errors we must first of all overcome our infatuation with the material revolutions. (Before it is Too Late, pp. 117–18)

A Fundamental Revolution in the Way We Think and Live

Peccei: Only recently has the appearance of the patent excesses and negative side effects of our modern civilization begun to shake the blind trust heretofore placed in it and in those who were supposed to know how to guide it. As is the case when one starts to examine a complex situation in greater depth, we discovered all sorts of things— some good, some not so good and some really bad—that had previously gone unnoticed. It thus became evident that, in some instances, the price the world is paying for the benefits derived from the material revolutions is far too high. Furthermore, it revealed that quite a few of these instances are by no means marginal but have a very major bearing on humankind’s future—its happiness, its quality of life and even perhaps its very survival.

We are all beginning to perceive how unbalanced our condition has become. We have the feeling that we ourselves lack internal balance and that to get materially richer we have in a way become spiritually, morally and philosophically poorer. We are starting to see how perilously lopsided our societies are because even our material benefits, welfare and progress are most unevenly distributed among and within nations and because the fate of billions of people lies in the hands of very small privileged elites who call the tune that, willy-nilly, everybody else must dance to. And it is now dawning on us that we are dangerously on the wrong foot with nature too and can no longer rely on it to support our sprawling enterprise and absorb all we are doing to make our position ever more formidable. As we perceive all this, realizing that never before has the world been torn by so many marked disequilibria, we hope and pray that something can be done to reestablish a modicum of dependable balance within our inner selves, within our societies and within our environment.

Ikeda: It is certain that disequilibria within humankind have brought about the imbalance you mention in society and the environment. Many people do try to restore balance but in general their efforts are directed to such stopgap measures as discovering a replacement for some natural resource that threatens to be exhausted or to correcting flaws in social systems by evolving new systems. It is safe to say that practically no one adds to these measures consideration of the need for a fundamental revolution in the way we human beings think and live. Retarding any change or breakthrough in the prevailing situation, the mass of humankind is hurtling at a steadily increasing speed along a path to disaster. Scientific technology advances at a dizzying rate year after year, and each new achievement is greeted as something worthy of uncritical congratulation and unconditional joy.

We are like a fearless child infatuated with the excitement of speed, stepping harder and harder on the accelerator of an automobile. A knowledgeable adult would take into account the possibility of curves or cliffs ahead and would regulate his speed to the situation and to his own ability to turn the wheel at the time of an unexpected crisis. But the child plunges ahead unaware that his situation is one demanding immediate change. In the case of humankind, that change is the human revolution.

Peccei: Extricating ourselves from the dangerous stricture in which we have become enmeshed by imprudently racing ahead in this way without knowing where we were actually going or whether we will be able to control our speed and direction is the great problem of our time. It is a problem that requires, first and foremost, a supreme cultural effort to understand why we have got ourselves into such a predicament and then to form a clear vision of the remedial philosophy of life and practical action best suited to permit us to regain safe ground for our march into the future. I maintain that this indispensable evolution can be triggered and accomplished only by relying on a strong, innovative humanism. This alone can provide the countervailing inspiration and force capable of challenging, taming and then guiding to good ends our triumphant but rudderless ‘progress.’ Such a humanism is the essence of the human revolution that can give meaning and finality to the material revolutions we have adventurously launched, propelling humankind into a bewitching but hazardous new phase of its venture.

Ikeda: I gradually become more convinced that what you call a ‘strong, innovative humanism’ is what Buddhism calls the human revolution. Human beings are easily led astray by the greed, anger and foolishness I mentioned earlier and are tossed about by the immensity of their own fates, or karmas. Like a rudderless boat in a storm we are dashed in totally unexpected directions. For instance, though perfectly well aware of the importance of preserving it, blinded by the attractive advantage of the moment, we often destroy or pollute parts of the natural environment. Or, as history has all too often demonstrated, while desiring peace, human beings frequently arm themselves to the limit and then, for some not always significant reason, plunge themselves into bloody war. Strong, innovative humanism is certainly necessary if we are to combat the deep, invisible currents of fate that are always at play in both individual lives and society as a whole.

Buddhism teaches how to bring forth and manifest in daily life the great universal self, or Buddha nature, that lies at the innermost level of each individual human life. The Lotus Sutra states that the Buddha nature is called Myoho-renge-kyo, the Mystic Law, and sets forth the ideal of the bodhisattva who acts compassionately to put this Mystic Law into practice.

In chapter 15 of the Lotus Sutra, four great bodhisattvas head a vast assembly of other bodhisattvas who rise up from the earth to be entrusted with the task of carrying the teachings to all sentient beings. Nichiren said that these bodhisattvas should be regarded not as people who once lived, but as characteristics of a life manifesting the Buddha nature. Their names and the traits they stand for indicate that this is true: ‘Superior Practices’, ‘Boundless Practices’, ‘Pure Practices’ and ‘Firmly Established Practices’. A life that manifests the Buddha nature and is characterized by conduct that is superior, boundless, pure and steadfast is one in which the stance you refer to as innovative humanism has been adopted and one that has undergone what we refer to as the human revolution. (Before it is Too Late, 119–21)

Merely Living Is Not Enough

Peccei: Certainly one of the objectives of the revolution I advocate is to prepare people to cope better with the complexities of the contemporary world and its artificiality, the new interrelations of everything with everything else and the unaccustomed challenges it poses to them individually and collectively—be they rich or poor, in the East, the West, the North or the South.

In past epochs, our predecessors undoubtedly had easier tasks to solve and could afford to make more mistakes. They apparently succeeded in doing remarkably well on the whole, in spite of their more restricted knowledge and scantier means. Even looking a long way back, we are amazed at how primitive people who knew very little about their hunting grounds or valley, and nothing about what lay beyond, managed to gather enough experience and develop enough wisdom to subsist, making good use of the sun, rain, winds and seasons, and getting along with all the plants and animals in the vicinity, including potentially harmful ones like snakes. We have transformed the earth to suit our needs, eliminating or domesticating most of the other living creatures and crowding every nook and cranny of the globe with machines and devices that can be far more dangerous than snakes, but we have yet to learn how to live harmoniously with this changed world—or even with one another. Nevertheless, billions and billions of us must live in it and must find ways to do so peacefully. Only the human revolution can teach us how.

However, merely living is not enough. Man must aim at being more than just a welfare-oriented biological organism who fares well economically by exploiting Nature’s bounties, thanks to his ingenuity in devising all kinds of sophisticated and powerful artifacts. By birth, he is more than just a consumer and a producer. He is a spiritual, dreaming creature, who loves myths and seeks to communicate with his God; he is a playful being, a poet, an inventor and an artist with immense curiosity and multiple skills, who deserves to be much more than the mere companion and master of his tools.

Only the human revolution can unearth our inner potential and make us feel fully what we really are and behave accordingly; only it can show us how to utilize our computers and satellites, our engines and instruments and our nuclear reactors and electronic gadgetry to commune better with our fellow humans and our entire Universe. It is this revolution alone that can make us see how important it is to survive in order to have a life worth living both for its own sake and as a means to prepare responsibly and compassionately a way of life for the generations of those who will follow us.

Ikeda: Once again, I sense a close parallel between what you say and certain Buddhist teachings. You say, “merely living is not enough,” since man must try to be more than a “welfare-oriented biological organism.” In Buddhist thought, human beings content to live biologically without attaining a higher state of development are confined to the six lower asura classes of existence (hell, hungry spirits, animals, asuras, human beings and heavenly beings) and are still bound to the cycle of transmigrations. Those who have undergone the human revolution belong in the four classes of holy men: shravakas, who attempt to reach eternal truth from the teachings of enlightened beings like the Buddha; pratyeka-buddhas, who attain truth from observing and meditating on natural phenomena on their own; bodhisattvas, who, while working for their own enlightenment, strive to help other beings as well; and finally Buddhas, who embody the eternal truth and have immense compassion for all beings. (Before it is Too Late, 122–24)

Before it is Too Late

Ikeda: All progress along a wrong course takes us farther from correct destinations. Clearly, getting on the right course is of the utmost importance. The thing that is most laudable in humanity is not going far fast, but choosing the correct direction in which to travel. Shakyamuni, his disciples, Confucius, Socrates, Plato and many others of the great human beings of the past commanded a much smaller volume of knowledge and enjoyed much less physical abundance than are available in modern society. But they knew how human beings should live and themselves lived in a more correct, downto- earth way than we do. We must prize them and attempt to emulate them spiritually in all we do because they possessed something incomparably more profound than modern man possesses.

Even today, it is the people who, without regard for wealth and fame, work and struggle with pleasure for their families and friends even in the face of the spiritual malaise characteristic of our highly materialistic, techno-scientific society, are the happiest. And though individual human beings cannot ensure rapid and far-reaching advances, they—and only they—can bring about their own changes of course. As the number of its members who put themselves on the right track increases, all of society will gradually swing round to a course centered on human beings and human dignity.

Peccei: I think, in conclusion, that the severity of our plight can no longer be denied and that the warning we and others untiringly give about the extreme gravity of the global situation and trends, and the absolute need to stop and reverse them must not be ignored. After making this premise unequivocably clear, I want to reiterate with equally firm conviction that it is within our power to turn the tide. There can be no doubt that our generations, who are responsible for conducting human affairs at this historical juncture, possess all the knowledge and means to overcome the obstacles and negative circumstances that have made our situation difficult all over the world and to reverse the downward drift of the human condition. Failure to recognize the growing grimness of the state of the planet would be irresponsible, but failure to believe that we possess the objective possibility of improving that state or refusal to exert supreme effort to bring about such a change would be even worse. Both attitudes must be condemned as a capital mistake that would have unfathomable consequences for future human history.

All of us can contribute to avoiding these mistakes being made. And since the human revolution is the key to positive action leading to the adoption of a new course and the revival of human fortunes, we must do whatever is in our power to help set it in motion—before it is too late. (Before it is Too Late, 146–47)

Aurelio Peccei

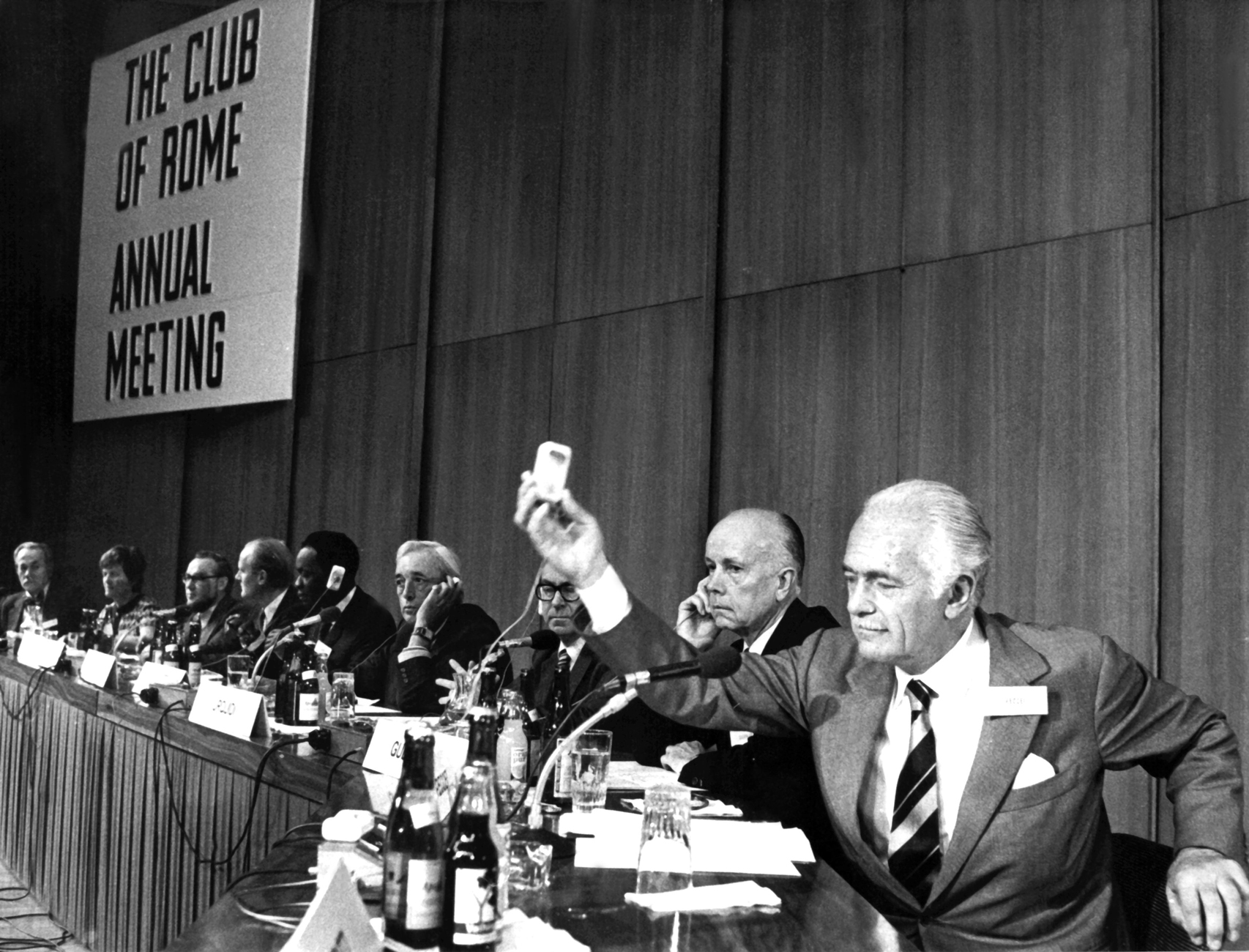

Aurelio Peccei (1908–84) was an Italian industrialist and scholar, best known as the co-founder of the Club of Rome in 1968. Born in Turin, Italy, in 1908, Peccei received his doctorate in economics from Turin University in 1930. As a member of the Italian Resistance movement during World War II, he was imprisoned in 1944 for 11 months. While he endured terrible torture in prison, he never lost hope in humanity.

In an essay that Ikeda Sensei wrote about his recollections of his meetings with Dr. Peccei, he recalls:

Dr. Peccei conceded that he suffered terribly, but also acknowledges that the ordeal he underwent strengthened his convictions. He also found friends whom he knew he could trust absolutely. Ironically, he learned a lot from his fascist captors, he said. He smiled, shrugged and added that, for that reason, he was now prepared to forgive them. …

In prison he experienced the foulest depths of human evil and, at the same time, the loftiest heights of human nobility. He realized that there was a tremendous force within us seeking good. It may be asleep, but it is there. That was his great awakening. (December 2000 Living Buddhism, p. 44)

After the war, Dr. Peccei became chairman of Fiat and president of Olivetti, while also being active in organizations like the World Wildlife Fund, Friends of the Earth and the International Ocean Institute. His books include The Chasm Ahead (1969), The Human Quality (1977) and One Hundred Pages for the Future (1981).

Before it is Too Late

In this dialogue, Before it is Too Late, Aurelio Peccei and Daisaku Ikeda examine questions under three broad headings: man and nature, man and man and the human revolution.

In this dialogue, Before it is Too Late, Aurelio Peccei and Daisaku Ikeda examine questions under three broad headings: man and nature, man and man and the human revolution.

Other topics in this book include:

—Inadequacy of material revolutions

—Global deforestation

—Food first, industrialization later

—Helping others have and use liberty

—Developing unused capacities

—Education and learning

To read the complete dialogue, order Before it is Too Late by Aurelio Peccei and Daisaku Ikeda (London: I.B. Tauris & Co., Ltd., 2009) at bookstore.sgi-usa.org.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles