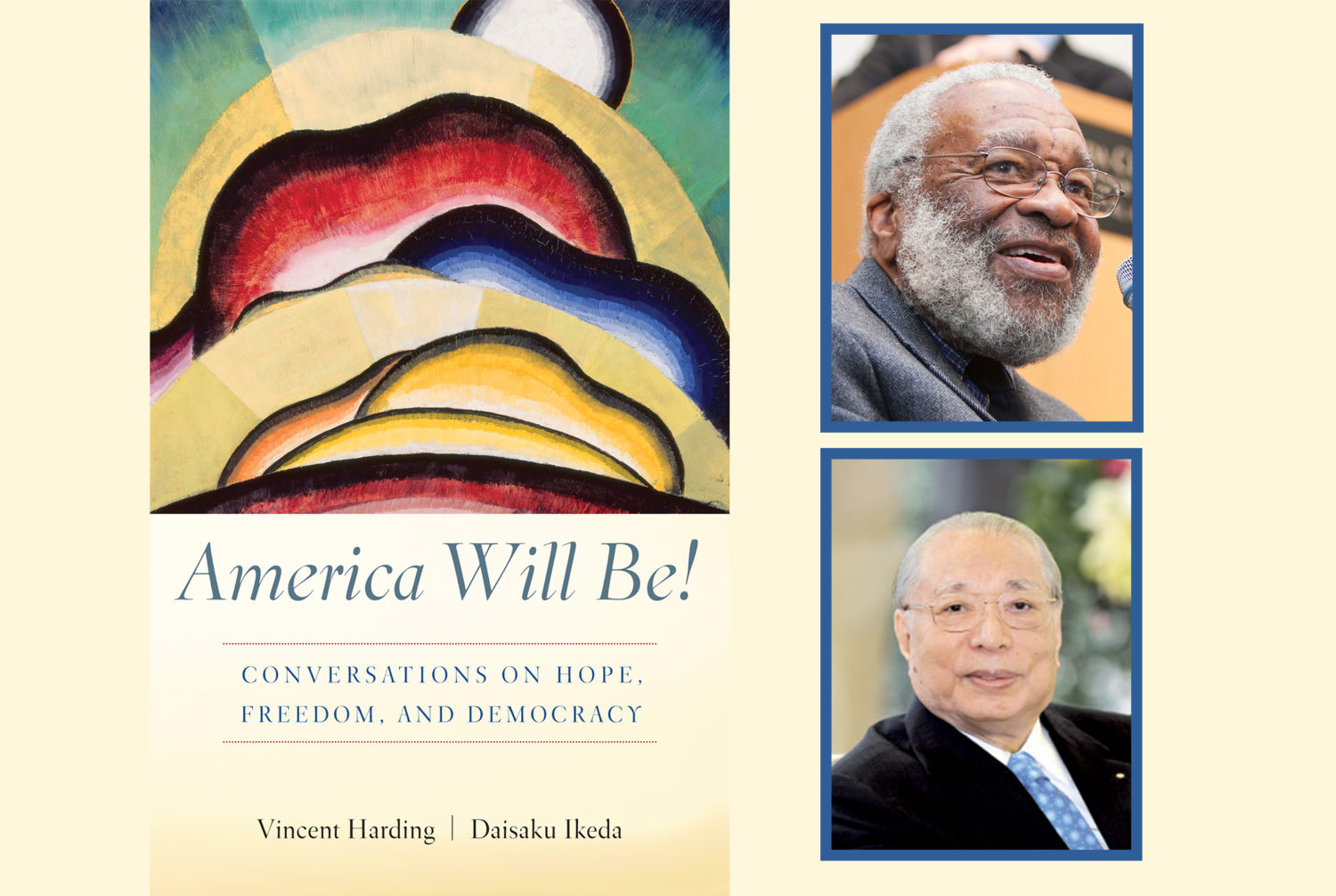

The following discussion between the late historian and civil rights champion Vincent Harding and Daisaku Ikeda offers insight into this question. These excerpts are taken from the book America Will Be! Conversations on Hope, Freedom, and Democracy, (pp. 85-88).

Daisaku Ikeda: Before [Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.] encountered [Mahatma] Gandhi’s philosophy, he had thought that Jesus’s message of loving one’s enemies was an individual ethic applicable only to interpersonal relationships. He had regarded the power of love as ineffectual in resolving social problems. King thought, for example, that a more realistic strategy of resistance was required in dealing with cruel, inhuman adversaries such as the Nazis or in resolving racial and ethnic conflicts.

However, studying Gandhi’s actions radically changed King’s thinking. As King explained:

Gandhi was probably the first person in history to lift the love ethic of Jesus above mere interaction between individuals to a powerful and effective social force on a large scale. Love, for Gandhi, was a potent instrument for social and collective transformation. It was in this Gandhian emphasis on love and nonviolence that I discovered the method for social reform that I had been seeking for so many months.[1]

Dr. King came to believe that love and nonviolence were the only realistic and moral weapons of use in fighting for freedom. As you mentioned earlier, religion and the movement for justice became closely interconnected.

The dictum to love one’s enemy is often interpreted as an instruction to not speak out against the enemy. However, this was not Dr. King’s understanding, was it?

Vincent Harding: King knew that one of the critical aspects of the teaching to love one’s enemy is the desire to not only free oneself from the hardships and struggles imposed by the enemy but, at the same time, to hope that the enemy has an opportunity to break out of the trap he or she has created for him- or herself. Essentially, this is compassion.

It is through compassion that we understand that an important part of our purpose in this world is to help others by whatever means possible—and assist our enemies in recovering from their illness and suffering …

Ikeda: … Nonviolent action is the struggle to elicit virtue and an awakening in the heart of the adversary. By transforming one’s spiritual state, one also transforms one’s opponent and society as a whole. It is, essentially, the struggle to save one’s opponent. This resonates profoundly with our Buddhist movement’s philosophy of human revolution.

Harding: … I remember Martin used to say: “We’re not called upon to like the enemy. We’re called upon to love the enemy.”

Even in our personal relationships, we don’t recognize sufficiently that to love is to seek the best for the other. Love is not a means of controlling the other or seeking what we want from the other. It means helping the other find out who he or she is meant to be. Love is also enabling the enemy to find out who they really are.

Ikeda: The Lotus Sutra provides, through Bodhisattva Never Disparaging’s example, a model for how the faithful should live. Bodhisattva Never Disparaging, who, as his name suggests, never scorned or ridiculed others, was a seeker of the Way who appeared long after the death of Awesome Sound King Buddha. This was a period in which the true teachings of the Buddha were in decline, a time of rampant discrimination and violence in society. In such an age, Bodhisattva Never Disparaging told the many people he met, “I have profound reverence for you,”[2] and taught that the precious life condition of Buddhahood was inherent in every person. But the arrogant, conceited people he lived among pelted him with verbal abuse and slurs, beat him with sticks and staves, and threw rocks and tiles at him.

Nevertheless, Bodhisattva Never Disparaging refused to be intimidated. Wisely avoiding the violence of his opponents, he continued to declare, “I have profound reverence for you,”[3] and carried on his practice. The bodhisattva continued to believe and spread the teaching that even within those who persecute, there abides the Buddha nature, the highest possible state of life. He demonstrated this essence of the Lotus Sutra in his life and religious practice.

Buddhism teaches: “If one befriends another person but lacks the mercy to correct him, one is in fact his enemy,”[4] and “One who rids the offender of evil is acting as his parent.”[5] If you care about your adversary, you must correct his wrong thoughts and doings in order to prevent his unhappiness or misfortune. It is in this sense that I understand your description of the principle of love and nonviolence.

Harding: … The goal of the struggle is not simply to eliminate injustice and oppression but to create a new reality. … King eventually began to speak of these ideas in terms of how we must create the “beloved community.” By this, he meant that the ultimate goal of the nonviolent warrior is to create a situation in which enemies can become brothers and sisters, and new relationships are established.

References

- Martin Luther King Jr., Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story, with a new introduction by Clayborne Carson (Boston: Beacon Press, 2010), pp. 84–85. ↩︎

- The Lotus Sutra and Its Opening and Closing Sutras, p. 308. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “The Opening of the Eyes,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 287. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles