As a young man, Ikeda Sensei studied a variety of world literature under the tutelage of his mentor, second Soka Gakkai President Josei Toda. The Books of My Youth is a collection of essays in which Sensei explores some of these works that, as he says, helped to form his life’s “spiritual framework.” The following excerpts capture some of Sensei’s key takeaways from several of these great works of literature. The Books of My Youth is available at bookstore.sgi-usa.org for $8.95.

The photographed cover of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms is of the same edition that Sensei studied under Mr. Toda.

On Plato’s ‘Apology’

On Plato’s ‘Apology’

It is said that throughout the vast collection of his writings, Plato uses his own name only three times. In Plato’s dialogues, however, his teacher, Socrates, appears frequently, speaking powerfully. It is widely known that there is not a single written word left by Socrates. As his disciple, Plato stayed in the background, constantly writing.

And he left in beautiful words for all of history Socrates’s legacy as a great philosopher and teacher of humanity. Without Socrates, there would have been no Plato. Without Plato, Socrates could not have enriched humanity. (Sensei, The Books of My Youth, p. 105)

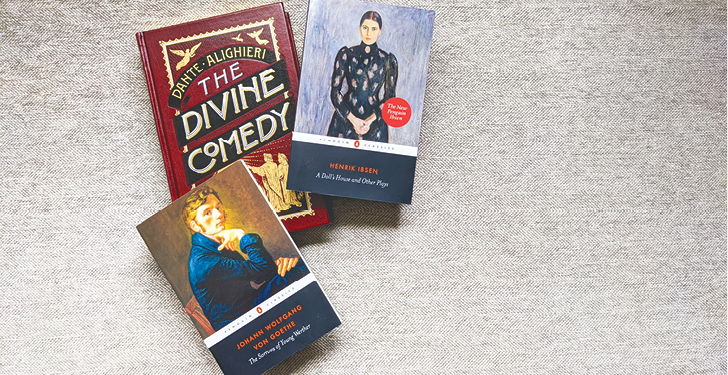

On Dante’s ‘The Divine Comedy’

On Dante’s ‘The Divine Comedy’

Although it came to be called “divine,” its theme is not limited to the divinity of the Christian God. Dante incorporates a vast array of the knowledge available in his day—including the classical literature of the ancient Greeks and Romans, the natural science of the Arabic world, and the flavor and landscapes of India and the Middle East. Some regard Dante’s work as an epic of encyclopedic scope. (pp. 6–7)

On Goethe’s ‘The Sorrows of Young Werther’

On Goethe’s ‘The Sorrows of Young Werther’

Life is another name for battling problems. In this poem, Goethe summarizes the idea that real satisfaction lies in taking one step after another amid the hard facts of life. One must not try to escape problems. The characters he created, portrayed and admired were but human beings who lived simply amid their realities. (pp. 167–68)

On Ibsen’s ‘A Doll’s House’

On Ibsen’s ‘A Doll’s House’

What Ibsen sought was not a revolution of systems or laws. More than anything, he hoped for a revolution of the human spirit, a liberation of the inner human being. “Belief in authority” resides in the inner realm, in the human heart. So long as that inner realm remains unchanged, no liberation or happiness can be achieved.

Ibsen had the insight that liberation on the essential level of the human being, in other words, a revolution to defeat people’s intrinsic “belief in authority,” begins with a fundamental revolution of the human being. (p. 184)

On Eiji Yoshikawa’s ‘The Romance of the Three Kingdoms’

On Eiji Yoshikawa’s ‘The Romance of the Three Kingdoms’

In my diary from those days, I find the entry from April 7, 1953, where I wrote, “Finished reading The Romance of the Three Kingdoms for the third time.” I had been absorbed in reading long works such as The New Tale of the Heike, New Brief Eighteen Historical Records and also The Water Margin. In my own way, I was putting into practice the guidance of my mentor, Josei Toda, who said: “Youth should read works about history. It is essential that they develop a historical perspective.” In my diary from around this time, I also find many entries in which I admonish myself to study harder. (pp. 130–31)

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles