The following essay by Ikeda Sensei was originally published in the July 7 issue of the Seikyo Shimbun, the Soka Gakkai’s daily newspaper.

First and foremost, I would like to offer my deepest sympathy to the people of Kumamoto and the rest of Kyushu [the southernmost of Japan’s four main islands] who have been affected by the recent destructive rains and flooding. On July 5, I did gongyo and chanted Nam-myoho-renge-kyo at the Soka Gakkai Mentors Hall (in Shinanomachi, Tokyo), praying earnestly for those who lost their lives and for the safety and well-being of all living in the impacted areas.

Record rainfalls have caused serious damage in communities throughout Kyushu and other regions of Japan. I am continuing to send prayers for everyone’s safety.

In July, our spirit as Bodhisattvas of the Earth burns with particular brightness. For us, the significance of this month dates back to July 16, 1260, when Nichiren Daishonin submitted to the nation’s ruler his treatise of remonstration, “On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land.”

The immortal concept of “establishing the correct teaching for the peace of the land” is completely Nichiren’s own. It is the profoundly compassionate lion’s roar of a single individual standing up to lead all people to enlightenment through the power of the Mystic Law.

In the Daishonin’s time, people were suffering bitterly due to a series of “unusual disturbances in the heavens, strange occurrences on earth, famine and pestilence” (“On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 6). This is similar to the adversity that humanity is facing today in its battle against the coronavirus pandemic.

In the opening passage of “On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land,” Nichiren writes, “There is hardly a single person who does not grieve” (WND-1, 6).

Throughout his treatise, the Daishonin focuses on those grieving the loss of beloved family members and friends. He acknowledges and empathizes with people’s anguish and suffering as if their pain were his own.

In the original manuscript of “On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land,” Nichiren uses in many places the Chinese character for “land” (also, “country” or “nation”) written with the element for “people” inside a square enclosure, rather than the characters using the element for “king,” or those suggesting a military domain, inside a square enclosure, which were more commonly used. This indicates that the Daishonin did not wish for the peace of the land as a faceless nation, but as a place where ordinary people live out their daily lives, and that his prayers were directed at the safety and well-being of those people.

In the same great spirit as Nichiren, first and second Soka Gakkai Presidents Tsunesaburo Makiguchi and Josei Toda, convinced that the time had come to remonstrate with the militarist authorities during World War II, took action for truth and justice. This led to their arrest on July 6, 1943.

Mr. Makiguchi died in prison for his beliefs the following year, and Mr. Toda, after spending two years behind bars, was released on July 3, 1945, just before the war’s end, emerging as an indomitable champion of the Mystic Law. That day and that moment was the dawn of the effort to realize Nichiren’s ideal of “establishing the correct teaching for the peace of the land” in modern times. Thus, the Buddhism of the Sun began to rise from the depths of tragedy of the cruelty and misery of war blanketing Japan.

Mr. Toda was 45 years old. So many of his fellow Soka Gakkai leaders from before the war had abandoned their faith, fearful of government persecution.

Feeling he could only rely on youth, Mr. Toda prayed for and eagerly awaited the emergence of such “young flag-bearers.”[1] He took one step after another, chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo into the wasteland of postwar Japan and calling forth, one by one, young disciples who shared the mission of Bodhisattvas of the Earth.

On July 1, 1950, five years after Mr. Toda’s release from prison, a youth meeting was held. Only about 20 people attended, but it was a profoundly significant event.

Numbers are not important; what matters is unity of spirit.

I wrote in my diary that day: “The youth have set sail toward the future’s storms and raging waves. I, too, will advance with my whole life.”

A large number of companies were failing at that time, and Mr. Toda’s businesses were also in dire financial straits. Forgetting the debt they owed their mentor, many people betrayed and deserted Mr. Toda.

I decided that now was the time for young people to stand up.

In “The Opening of the Eyes,” the Daishonin writes, “As mountains pile upon mountains and waves follow waves, so do persecutions add to persecutions and criticisms augment criticisms” (WND-1, 241). I recognized that this was the path that Soka mentors and disciples must travel to realize the great vow for kosen-rufu. The challenges ahead would only make us, the youth, stronger.

Even a single ordinary, unremarkable youth such as myself, I thought, could support his mentor through chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo based on the shared commitment of mentor and disciple. Such a youth could overcome all obstacles and lead the entire organization for kosen-rufu steadily forward.

That was my vow and my prayer.

“The greater the resistance waves meet, the stronger they grow”—with this resolve, I was determined to endure every hardship and demonstrate the victory of mentor and disciple, confident in the principle that “unseen virtue produces visible reward.”

The following year, 1951, having overcome the challenges that faced him, Mr. Toda was inaugurated as the Soka Gakkai’s second president (on May 3). A few months later, in July, he founded the young men’s division and the young women’s division (on July 11 and 19, respectively).

The Korean War (1950–53) was raging at the time. Mr. Toda, who the following year set forth a vision of global citizenship, taught the members of the newly established divisions that it was their noble mission to carry out kosen-rufu by realizing the ideal of “establishing the correct teaching for the peace of the land” not only in Japan but throughout Asia and the world.

I was a group leader then, striving hard on our organization’s front lines. Filled with passion and enthusiasm to expand our movement for kosen-rufu, I immediately went to Sendai in Tohoku’s Miyagi Prefecture. I have the fondest memories of working alongside our sincere members there.

At one discussion meeting, I confidently shared my personal experience in faith, including overcoming tuberculosis and helping Mr. Toda surmount his business difficulties. I recall that eight guests decided to join the Soka Gakkai that day.

Nichiren’s treatise “On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land” is written in the form of a one-to-one dialogue. The ultimate means for realizing the ideal of “establishing the correct teaching for the peace of the land” is to firmly establish in the heart of each person a steadfast commitment to justice.

The youth decided that all change had to begin with fostering understanding and connection with those around us. Our gathering of friendship and respect—valuing unity in diversity—is a powerful source of hope.

During the current unprecedented challenges of the coronavirus pandemic, youth division members throughout the world, who embody the principle of “from the indigo, an even deeper blue,” are striving with an indomitable spirit, summoning all their wisdom and courage to transform this crisis into a positive turning point.

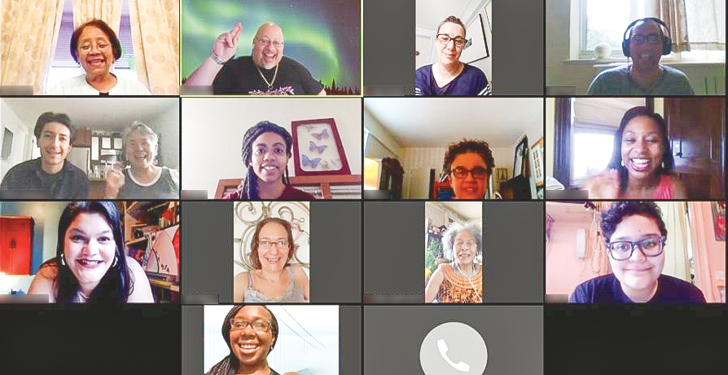

They are making good use of the phenomenal advances in technology in recent years and holding meetings online. Though they can’t meet face-to-face, they are able to see one another through video calls. It seems that, in some places, this has enabled even more members and friends to take part in activities.

Leaders are putting great energy into making these online gatherings as meaningful as possible for members. As a result, the participants are enjoying themselves and feeling inspired, and everyone is growing together.

Incidentally, this month in Brazil, which has been hit especially hard by the pandemic, 100,000 youth division members are working together in an ongoing effort to support and encourage their friends while positively contributing to society.

Mr. Toda, a skilled mathematician who always kept abreast of the latest developments in science and technology, often said that advances in transportation and communications technology were signs that kosen-rufu was close at hand. I am sure he would be delighted to see the creativity and ingenuity of today’s youth division members.

The worldwide advance of kosen-rufu is indisputable and happening faster than ever! Therefore, instead of being adverse to change, let us do our best, with young people in the lead, to imbue our ever-changing reality with the spirit of “establishing the correct teaching for the peace of the land,” of striving for peace and the happiness of humanity.

We are now presented with a wonderful opportunity to make the humanism of Nichiren Buddhism shine even brighter. There is no limit to the value we can create. This is especially true because the youth, who will carry on this mission into the future, have limitless power and potential.

Exactly 30 years ago, in July 1990, I visited the Kremlin in Moscow and had my first meeting with Mikhail Gorbachev, the former Soviet president, who played a central role in bringing an end to the Cold War.

I greeted him with the words “I have come to have an argument with you. Let’s make sparks fly, and talk about everything honestly and openly, for the sake of humanity.” President Gorbachev replied with a broad smile: “I, too, like honest and open dialogue. I feel as if we are old friends.”

In our more than 10 encounters, one of the major topics we discussed was that the greatest threat to the 21st century was division. I asked his thoughts about how we could overcome divisiveness, which seemed to spread everywhere like an invisible plague. President Gorbachev stressed that we must find the power to unite people.

One of the conclusions we also reached was the importance of optimism—believing that we can surmount every challenge, maintaining unconditional trust in the power of the human spirit and having faith in humanity’s future. These are the keys, we agreed, for overcoming all divisions and bringing the people of the world together.

As the disciple of Mr. Makiguchi and Mr. Toda, I have persisted in dialogue aimed at realizing the Daishonin’s ideal of “establishing the correct teaching for the peace of the land.” One result of this is that my writings, including dialogues I have engaged in with leading world thinkers in an effort to bridge cultures and civilizations, have been translated into 50 languages. They are on display in the Soka Gakkai Mentors Hall as an expression of my gratitude to our first two presidents.

Our Soka youth are kings and queens of dialogue, champions of the written and spoken word. They will carry on, into the 21st century, the spirit of unflagging optimism and faith in humanity that will vanquish the hopelessness of this age racked by mistrust and fear.

Thirty-five years ago, in July 1985, to commemorate the anniversary of the establishment of the young women’s division, I inscribed in calligraphy the Chinese character for “king” or “monarch.”

Nichiren writes:

The character “king” is written with three horizontal lines and one vertical line. The three horizontal lines represent heaven, earth, and humanity, and the single vertical line represents the ruler. … one whose presence pervades the realms of heaven, earth, and humanity and who does not waver in the slightest is called the ruler. (“White Horses and White Swans,” WND-1, 1063)

One who stands as an unshakable, central pillar is a “king,” a true champion.

Young people are easily swayed by their emotions. Nevertheless, even amid an unremitting succession of natural disasters, the youth of Soka are studying the supreme life philosophy of Nichiren Buddhism and, while grappling with their own problems and difficulties, striving courageously to fulfill their vow for kosen-rufu. They are a solidly united force exemplifying the resilience to overcome all hardships. They are noble pillars of peace, culture and education for global society.

Embracing the Lotus Sutra—which Nichiren describes as the “king of sutras” (“On Attaining Buddhahood in This Lifetime,” WND-1, 3) and likens to the “lion king” (“The Drum at the Gate of Thunder,” WND-1, 949)—become ever-victorious champions yourselves!

My dear young friends whom I trust wholeheartedly— be inspiring champions of youth, bright champions of hope, strong champions of invincible spirit and champions of justice who refute falsehood and error!

I call on you to advance together with me, regarding hardships as an honor and taking pride in the fact that Soka youth are champions of the spirit!

References

- A line from a verse in the “Song of Comrades,” written by President Toda. The verse in full reads: “I do not begrudge my life, / but where are the young flag-bearers? / Can you not see Mount Fuji’s summit? / Rally now, quickly, in growing numbers!” ↩︎

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles