This month, we commemorate 150 years since founding Soka Gakkai President Tsunesaburo Makiguchi’s birth. As an educator and religious man of conviction, dignity and integrity, he always strove to better the lives of his students and all people, challenging the tyranny of those in power and paving the way for humanity’s happiness. The following offers a glimpse into Makiguchi’s noble life and legacy.

Early Life Shaped by Struggle

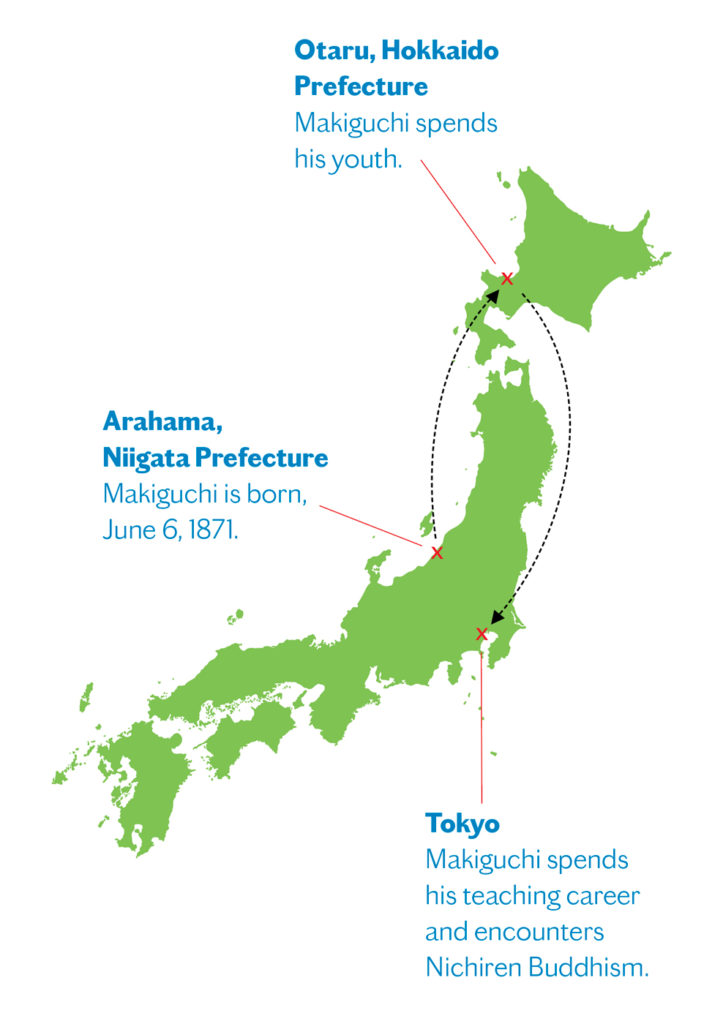

On June 6, 1871, Choshichi Watanabe was born the eldest son of Chomatsu and Ine Watanabe in Arahama, an impoverished fishing village in Niigata Prefecture, Japan.

He would later take the name Tsunesaburo Makiguchi and found the Soka Gakkai, a global community-based organization that promotes peace, culture and education rooted in the ideals of Nichiren Buddhism and respect for the dignity of life.

Before Choshichi was 3, his father abandoned the family. When he was 5, his mother remarried, and it was around this time that he was adopted by his aunt Tori and her husband, Zendayu Makiguchi.

In those days, only about a fifth of children in Arahama attended school, but Choshichi Makiguchi was fortunate to attend elementary school from age 7. Despite his good grades, his family’s poverty made it impossible for him continue his education, and he began working at age 11.

When he was 13, Makiguchi left Arahama and went northward to Hokkaido, where he worked at a local police department as an errand boy. Using every spare moment he had to read and study, he earned the nickname “Bookworm.”

Makiguchi’s work ethic, dependability and scholarly disposition impressed the chief of police, who supported him in entering Hokkaido Normal School in 1889. In 1893, at age 21, he changed his name to Tsunesaburo and began his career as a teacher at the Hokkaido Normal School, where he taught for the next eight years. He became a respected educator and used his spare time to refine his theory on geography.

In 1895, he married Kuma, and together with their children, in 1901, they moved to Tokyo.

Teaching Geography to Connect Students to the World

Makiguchi believed that the study of geography could be used as a central, unifying point for the elementary school curriculum. He used things familiar to students, such as food and clothing, to explore their place of origin and the landscape, climate and people in those places. He condemned narrow-minded nationalism and promoted a global perspective, which was contrary to the prevailing mood at the time. After a decade of forming his theory on geography, in 1903, he published his first major work, The Geography of Human Life, at age 32.

Although unknown in this field, scholars praised Makiguchi’s 1,000-page book as a work that “changed the face of the field of geography in Japan.”[1]

Over the next several years, he was committed to creating learning opportunities for those who faced various obstacles in receiving an education. For example, he taught geography at an academy for students from China. In Japanese society at that time, it was commonplace for people to look down on Chinese residents. Yet Makiguchi treated every student with the utmost respect. His students would later translate and publish the Chinese edition of The Geography of Human Life.

Makiguchi also founded the Japan Society for Further Education for Young Women, which provided secondary education correspondence courses for women who faced socio-economic challenges advancing their education.

A Warm, Caring Educator and Relentless Advocate for Students’ Happiness

From age 42, Tsunesaburo Makiguchi served as principal for a number of Tokyo schools, reforming education and developing some of the city’s most outstanding public schools.

As a principal at Taisho Elementary School, he made extra effort to care for underprivileged children with challenging circumstances, visiting families of children who were not attending school. Many parents that he visited couldn’t read or write themselves.

He also refused to give those with money or power any preferential treatment. When a powerful figure asked him to give preferential treatment to their child, Makiguchi refused. As a result, he was forced to resign.

He was then sent to Nishimachi Elementary School. There, he met Josei Toda, a young teacher who had moved from Hokkaido to Tokyo and was serving as a substitute teacher. Makiguchi was 48 and Toda was 19. This was the start of their lifelong bond as mentor and disciple.

Just after three months as principal there, Makiguchi again incurred the authorities’ wrath and was forced to resign. Despite students, teachers and parents protesting his dismissal, he was transferred to Mikasa Elementary School. Toda transferred with him.

At Mikasa, Makiguchi moved his family into on-campus housing to be on call for the students 24 hours a day. He again strove to convince parents how important it was for their children who were not attending classes to receive an education. His impassioned words often resulted in parents promising to send their children to school.

And despite Makiguchi’s financial struggles to feed his own eight children, he prepared simple meals for students who came to school hungry, initiating a free-lunch program for low-income families.

His concern for his students knew no bounds. On some days, he would carry the smaller students on his back while leading older ones by the hand to take them home. On cold winter days, he would prepare warm water to bathe students’ chapped hands. He also provided school supplies for students who could not afford them.

Makiguchi’s educational aim was simple: the happiness of every student. His perspective was undoubtedly formed by his own childhood struggles as well as observations of his most destitute students.

In contrast to his warmth as an educator, as an administrator, he was relentless in his critique of the Japanese education system, which promoted rote memorization and coercive learning. He went above and beyond to ensure the safety, good health and well-being of his students.

Through contemplating the nature of happiness, he concluded that true happiness lies in the ability to create value amid the challenges of life.

Value-Creation Education Society

In 1928, after being introduced to Nichiren Buddhism by another principal, Makiguchi realized that Nichiren Daishonin’s teaching was the final missing piece to his theory of value.

Describing his encounter with Nichiren Buddhism, he writes:

When I eventually made the firm determination to adopt this faith, I was able to affirm, in the actualities of daily life, the truth of these words of Nichiren Daishonin: “When the skies are clear, the ground is illuminated. Similarly, when one knows the Lotus Sutra, one understands the meaning of all worldly affairs.”[2] And with a joy that is beyond the power of words to express, I completely renewed the basis of the life I had led for almost 60 years. The sense of unease, of groping my way in the dark, was entirely dissipated; my lifelong tendency to withdraw into thought disappeared; my sense of purpose in life steadily expanded in scope and ambition, and I was freed from all fears; I became possessed with the irresistible and bold desire to effect the reform of national education with as much haste as was humanly possible.[3]

On November 18, 1930, his theory of value was published as a book titled The System of Value-Creating Pedagogy. This date later became the founding date for the Soka Kyoiku Gakkai (Value-Creating Education Society), the forerunner of the Soka Gakkai.

Josei Toda, his now trusted disciple, had worked tirelessly to organize and compile Makiguchi’s many notes, taking full responsibility for the book’s publication.

The Development of the Soka Kyoiku Gakkai

By 1932, the Soka Kyoiku Gakkai, which began as a society to reform education, had developed into a movement to reform society through the promotion of Nichiren Buddhism. Makiguchi dedicated himself to the group’s activities and the propagation of Buddhism, on some occasions traveling days to share Buddhism with a single individual.

With the start of World War II, the militarist government sought to enforce state-sponsored Shinto practices centered on the divinity of the emperor. Soon, Makiguchi’s religious activities attracted attention and attempts were made to suppress the Soka Kyoiku Gakkai’s movement to empower ordinary people.

As a “thought criminal,” Makiguchi endured the secret police’s monitoring of activities. After he refused to accept the Shinto talisman and submit to the absolute divinity of the emperor, he and Toda were arrested and imprisoned on July 6, 1943.

Makiguchi was in his 70s. Despite harsh interrogations, he never recanted his beliefs. In fact, out of the 21 detained Soka Kyoiku Gakkai members, only Makiguchi and Toda never renounced their faith.

In prison and during interrogations, Makiguchi shared Nichiren Buddhism and his theory of value with his jailers. He wrote postcards to encourage his family, assuring them that he remained undefeated. He wrote, for instance:

For all of us, faith is the most important thing. We may consider this a great misfortune, but it pales into insignificance when compared to what the Daishonin endured. It is important to understand this fact clearly and to strengthen your faith more than ever. We live lives of vast and immeasurable benefit and cannot possibly resent or regret a situation such as this one. From my experiences to date, I know clearly that, just as it states in the sutra and [the writings of Nichiren], “poison will be turned into medicine.”[4]

In another letter, he proclaims: “Depending on one’s state of mind, even hell can be enjoyable.”[5] His towering life state was imperturbable.

On November 18, 1944, after a year and four months in prison, Makiguchi died of malnutrition. Only a few people attended the funeral of this noble man, who had uncompromisingly dedicated his life to the happiness of humanity.

Makiguchi’s Legacy Lives On

Two years after their arrest, Josei Toda was released from prison on July 3, 1945. To avenge the death and prove the greatness of his mentor, Toda set out to rebuild the Soka Gakkai.

Under Toda’s leadership as second Soka Gakkai president, together with his disciple, Daisaku Ikeda, the Soka Gakkai became a movement 750,000 households strong.

Ikeda Sensei, who became the third president of the Soka Gakkai, established the Soka Gakkai International that today comprises over 12 million members in 192 countries and territories.

Underlying the Soka Gakkai’s astounding growth is the focus on one-to-one dialogue and small-group discussions—a tradition initiated and established by Makiguchi.

Furthermore, Ikeda Sensei established the Soka schools system, ranging from kindergarten- to university-level, as well as Soka education institutions around the world. This human-centered educational approach is rooted in the ideals of Nichiren Buddhism and Makiguchi’s educational aim: to foster students who can create value amid all circumstances and lead compassionate, contributive lives.

Despite passing away in the confines of prison, Tsunesaburo Makiguchi’s magnanimous spirit and legacy continues to grow around the world, living on and flourishing through the efforts of SGI members and Soka graduates who are leading fulfilling lives and striving to bring about a century of peace.

Timeline of Tsunesaburo Makiguchi’s life

June 6, 1871: Born Choshichi Watanabe in the village of Arahama, Niigata Prefecture, Japan.

June 6, 1871: Born Choshichi Watanabe in the village of Arahama, Niigata Prefecture, Japan.

May 9, 1877: Adopted by Zendayu Makiguchi and his wife, Tori.

April 20, 1889: Gains entrance to the Hokkaido Normal School in Sapporo, Japan.

March 31, 1893: Graduates from the Hokkaido Normal School and starts teaching.

April 24, 1901: Left Sapporo for Tokyo together with his wife and children.

October 15, 1903: Publication of The Geography of Human Life.

April 4, 1913: Appointed principal of Tosei Elementary School.

January 1920: Makiguchi and Toda meet at Nishimachi Elementary School. Toda is employed as a substitute teacher there.

June 1928: Makiguchi is introduced to Nichiren Buddhism.

November 18, 1930: The System of Value-Creating Pedagogy is published. This date is also considered the founding of the Soka Kyoiku Gakkai.

July 6, 1943: Makiguchi and Toda are detained and imprisoned as thought criminals.

October 13, 1944: Writes his final postcard to his daughter-in-law Sadako and his wife, Kuma.

November 17, 1944: Transferred to the prison hospital, insisting he walk rather than be carried.

November 18, 1944: Dies in prison of malnutrition at age 73.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles