by Karen Blake

Houston

I met Winston in December 1973 in the Brooklyn apartment of a mutual friend. He was recruiting locally for the U.S. Army. I was there because our friend, a co-worker, invited to take me to a Buddhist meeting, my first, at a nearby district member’s home. Deeply moved by the members’ enthusiasm, I resolved to attend many more meetings, as many as possible. My friend’s apartment became the regular rendezvous before going to our district meetings. This was the place this young man, Winston, and I got to talking.

By the time we started dating, I was gung-ho about SGI activities, traveling by bus and subway after work seven days a week and going to my first Buddhist convention in San Diego a month after receiving the Gohonzon.

Before taking up Buddhism, I had zero courage, zero compassion and zero wisdom. I was terribly excited about my practice but new to it, and my heart was not abreast of my words. I could share about my faith and the lofty philosophy of human revolution and, in the same breath, disparage a friend. Winston was honest and straightforward and would check me in these moments, but gently.

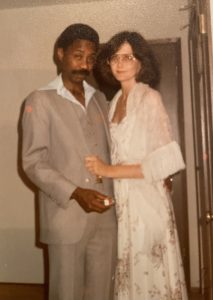

In 1979, I married him, knowing full well that married life with a military man would be no walk in the park. Indeed, for some time I walked alone. He was on deployment in Korea when I accepted a job transfer to Texas, where we had no family to speak of. He was in Korea still when I gave birth to our son. He was on duty while I fought an uphill battle for recognition at work in the first year of motherhood and when my doctor diagnosed my chronic fatigue as a symptom of thyroid disease. Nam-myoho-renge-kyo got me through all of this.

Nam-myoho-renge-kyo and the thought of this stern and gentle man coming home at last, to be a husband and a father. So you can imagine my dismay when he did come home in 1981, stern as ever but missing his gentle half. I felt defeated and hopeless, fearing we would never restore our relationship. Over time, I put up walls and tuned him out.

One day in Houston, I came home and Winston greeted me with a question: “Is this how Buddhists behave?” Though his delivery needed work, I knew deep down that there was truth in what Winston was saying. I sought advice from seniors in faith, and each time the guidance got a little shorter, until eventually, it boiled down to a single word: appreciation.

Ironically, our major point of contention was my financial contributions to the SGI. I can see how these contributions alongside all my talk of showing appreciation through offerings must have struck him as the most glaring discrepancy between the tenets of my faith and my approach to him.

Through chanting, studying, sharing the practice and taking part in financial contribution, I had developed a strong sense of appreciation for my life, with all its challenges. All of them, it seemed, except one. Why could I not feel appreciation for my husband? This certainly was not how Bodhisattva Never Disparaging would feel.

One senior advised that I say thank you to Winston every day, many times before noon. But I couldn’t help counting out each one behind my back, making the effort less sincere.

Another advised that, before going out to an evening activity, I set the table with a placemat, a glass, a napkin and silverware, with a note reading: Dinner is in the microwave. Actually, this touched his heart and was a breakthrough of sorts. Though he didn’t say anything at the time, years later, I came home to find he’d done the same for me. It was clear proof of the power of offering. What had to change was me, not him; my sincerity determined everything. I upped my financial contribution and my prayer.

Over the years, we did have breakthroughs, hard-won chinks in the wall between us. But the wall itself never fell. Still, I beat at that wall with my daimoku, to break through to deeply appreciate my husband.

Then, in January 2017, I fell in the bathroom and broke both my wrists. Suddenly I couldn’t do anything on my own. I couldn’t wash my face, comb my hair, make meals.

Winston rose to the occasion. He was incredible. All the softness and generosity I remembered from our early days came rushing back. Everything one could ask for, he did for me. He even colored my hair. Not his line of work: I looked like Alfalfa after the blowdrying. All I could do was appreciate his sincerity.

“You have my back,” he told me. “I want you to know I have yours too.”

And a sister in faith mused, “You know, Karen, next time you chant to find appreciation, do it with the caveat without bodily injury.” Jokes aside, everyone who saw us knew we had won.

Recently, while he was watching a baseball game, I asked Winston if he’d like to join in making his own sustaining contribution. I tried to play it cool when he said yes. Ours is a story of transforming suffering into joy based on courage, compassion and wisdom.

Today, Winston sees me off to SGI meetings with a full tank of gas, schedules dinner to work around my Zoom visits with the members, is a wonderful human being, a compassionate companion. Today, I know a profound appreciation for my life that I could not have savored without him.

If … we engage in our Buddhist practice with a spirit of goodwill toward others and a desire to praise and support everyone, we will experience a deep sense of joy and appreciation. … In fact, this is proof of our human revolution and the true embodiment of happiness.

Ikeda Sensei, The New Human Revolution, vol. 26, p. 301

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles