Fifty years ago this month, Ikeda Sensei began his dialogue with the British historian Arnold J. Toynbee. More than a conversation—a mere exchange of sentiments, observations and ideas—theirs was a dialogue—a collaborative search for common ground and a roadmap to aid future generations in surmounting the most pressing obstacles to world peace.

In this sense, what we might consider a conversation and a dialogue are poles apart. To be sure, Sensei would later define dialogue in its truest form as “a ceaseless and profound spiritual exertion that seeks to effect a fundamental human transformation in both ourselves and others.”[1]

In his 1993 speech at Claremont McKenna College titled “Radicalism Reconsidered,” Sensei notes that just as radicalism is fated by its nature to resort to violence, the most potent weapon in the arsenal of the gradualist—one who is committed to self-motivated, lasting change—is dialogue.[2]

Though our efforts for peace take place on a different scale, we can apply these same lessons to our own challenges and conflicts, and in the process, polish our humanity.

From Sensei, here are six keys to having genuine dialogue.

1. Through Sustained Engagement, We Can Cultivate The Positive Qualities In Ourselves And Others.

When we learn to recognize what Thoreau refers to as “the infinite extent of our relations,”[3] we can trace the strands of mutually supportive life and discover there the glittering jewels of our global neighbors. Buddhism seeks to cultivate wisdom grounded in this kind of empathetic resonance with all forms of life.

In the Buddhist view, wisdom and compassion are intimately linked and mutually reinforcing. Compassion in Buddhism does not involve the forcible suppression of our natural emotions, our likes and dislikes. Rather, it is the realization that even those whom we dislike have qualities that can contribute to our lives and can afford us opportunities to grow in our own humanity. Further, it is the compassionate desire to find ways of contributing to the well-being of others that gives rise to limitless wisdom.

Buddhism teaches that both good and evil are potentialities that exist in all people. Compassion consists in the sustained and courageous effort to seek out the good in all people, whoever they may be, however they may behave.It means striving, through sustained engagement, to cultivate the positive qualities in oneself and others. Engagement, however, requires courage.[4]

2. Conquering Our Own Prejudicial Thinking Is A Necessary Precondition For Dialogue.

Why was Shakyamuni able to employ language with such freedom and to such effect? What made him such a peerless master of dialogue? I believe that his fluency was due to the expansiveness of his enlightened state, utterly free of all dogma, prejudice and attachment. The following quote is illustrative: “I perceived a single, invisible arrow piercing the hearts of the people.” [5] The “arrow” symbolizes a prejudicial mind-set, an unreasoning emphasis on individual differences. …

The conquest of our own prejudicial thinking, our own attachment to difference, is the necessary precondition for open dialogue. Such discussion, in turn, is essential for the establishment of peace and universal respect for human rights.[6]

3. Actively listen to the other person.

There are few opportunities for meaningful dialogue with others in today’s fast-paced, disconnected society. Instead of enjoying genuine communication, many are suffering in isolation.

That’s why it’s so important to put aside our differences and really listen to others, sharing their pains and sufferings as fellow human beings. The caring heart capable of listening in this way has the power to open people’s minds, to dispel anxiety and to heal mental wounds. It takes a human heart to touch a human heart.

“When you’re suffering, I hurt, too.” By engaging in dialogue in this spirit of empathy—what is called in Buddhism “shared suffering”—both parties are strengthened and elevated.[7]

4. Seek to understand the other person.

It can’t be called a dialogue where one person constantly interrupts while the other is trying to express an opinion and then lays down sweeping conclusions.

Even if you think that what someone is saying is a bit odd, rather than constantly raising objections, you should have the broad-mindedness to try to understand his or her point of view. Then the person will feel secure and can listen to what you have to say.

In that sense, the Buddha is truly a master at dialogue. Shakyamuni and Nichiren Daishonin had such heartwarming personalities that just meeting them must have given people a sense of immense delight. And that’s probably why so many took such pleasure in listening to their words.[8]

5. Resolving Problems Takes Courage.

Dialogue is not limited to formal debate or placid exchange that wafts by like a spring breeze. There are times when, to break the grip of arrogance, speech must be like the breath of fire. Thus, although we typically associate Shakyamuni and Nagarjuna only with mildness, it was the occasional ferocity of their speech that earned them the sobriquet of “those who deny everything” [9] in their respective eras. …

Nichiren’s faith in the power of language was absolute. If more people were to pursue dialogue in an equally unrelenting manner, the inevitable conflicts of human life would surely find easier resolution. Prejudice would yield to empathy and war would give way to peace. Genuine dialogue results in the transformation of opposing viewpoints, changing them from wedges that drive people apart into bridges that link them together.[10]

6. True dialogue must be carried through to the end.

It is only within the open space created by dialogue whether conducted with our neighbors, with history, with nature or the cosmos that human wholeness can be sustained. The closed silence of an isolated space can only become the site of spiritual suicide. We are not born human in any but a biological sense; we can only learn to know ourselves and others and thus be “trained” in the ways of being human. We do this by immersion in the “ocean of language and dialogue” fed by the springs of cultural tradition. …

To be worthy of the name dialogue, our efforts for dialogue’s sake must be carried through to the end. To refuse peaceful exchange and choose force is to compromise and give in to human weakness; it is to admit the defeat of the human spirit. [11]

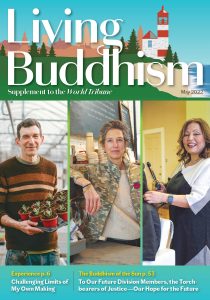

For more on the Ikeda-Toynbee dialogues, see the May 2022 Living Buddhism, pp. 12–27.

References

- Sept. 28, 2007, World Tribune, p. 2. ↩︎

- See A New Way Forward, p. 32. ↩︎

- Henry David Thoreau, “The Village” in Walden, The Selected Works of Thoreau, ed. Walter Harding, Cambridge ed. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1975), p. 359. ↩︎

- A New Way Forward, pp. 89–90. ↩︎

- J. Takakusu, ed., Taisho daizokyo (Tokyo: Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo Publishing Society, 1935), 24:358. ↩︎

- A New Way Forward, pp. 41–42. ↩︎

- The Inner Philosopher, p. 100. ↩︎

- The Wisdom of the Lotus Sutra, vol. 2, p. 197. ↩︎

- See Takakusu, ed., Taisho issaikyo, vol. 30. ↩︎

- A New Way Forward, p. 43. ↩︎

- Ibid., pp. 32–33. ↩︎

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles