by Edwin Franco

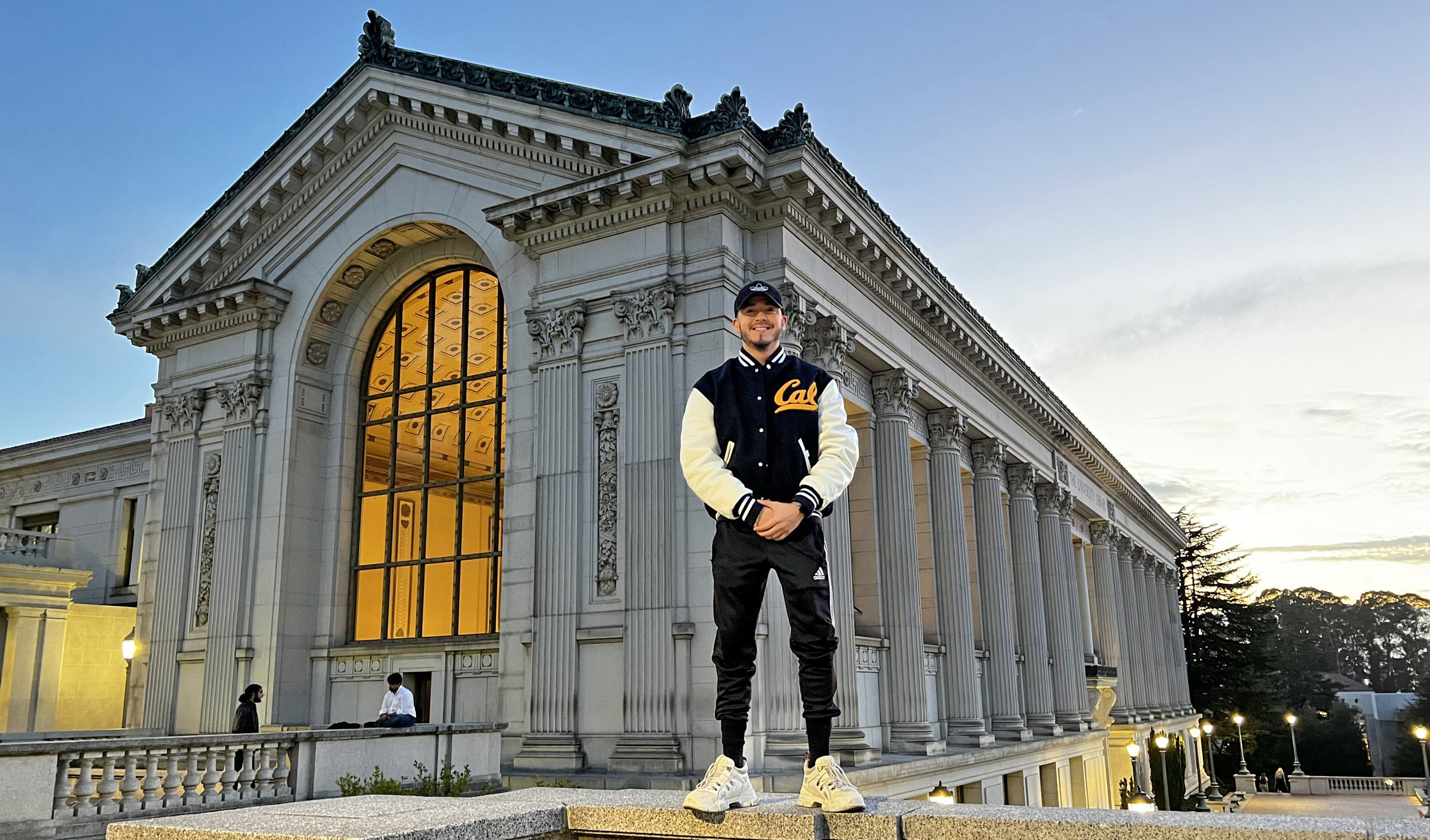

Berkeley, Calif.

I was born in Tijuana, Mexico, to a father who drank. Unhappy under his roof, my mother left, with my three siblings and me, when I was 5. She wanted something better for us but found herself in other marriages with men much like my father. Growing up, I saw anger vented in unhealthy ways and did not know, because I wasn’t shown, another way to vent my own.

My mother was diagnosed with cervical cancer my senior year of high school and would not live to see me graduate. She knew as much and told me, sitting bedside, her hand in mine, that she’d be watching over the ceremony.

“Yo se que háras cosas grandes en la vida,” she said. I know you’ll do great things.

By then I knew what I wanted to do. The kindness certain doctors showed her had inspired in me a love of medicine; the short-temperedness of others convinced me that I could, with training, do the job better. I wanted to uplift low-income communities as a physician.

But further schooling was impossible. As the eldest of four, it was up to me, together with my grandma, to put food on the table. I put my dreams aside and took a job as a bank teller, but I was furious. My mother had been young—we were young. It wasn’t fair to anyone. I took my anger out on friends and partners.

In 2013, a year after graduation, I met an American, married and moved to Palm Springs, California, where I could work and send money home while taking English as a second language (ESL)courses. Soon, however, the marriage became toxic. I left for school after a bad argument one morning in April 2016 and came home that evening to find my belongings on the curb—everything but the paperwork proving my U.S. residency. Living in my car, hardly fluent and without legal papers, I still managed to attend my ESL program. It was here that a fellow student introduced me to Nichiren Buddhism, telling me, when I asked why I should take an interest, that it would help me believe in myself.

I felt awkward at my first district meeting, listening to the chanting of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. Soon, though, I joined in and felt something, some change or hope or happiness—felt, for a moment, what it was to put anger aside. I continued chanting and coming to meetings, drawn by the incredible positivity there. I also participated in youth activities like taiko, Soka Group and Gajokai. The men’s and women’s division took me under their wings like a son, and I felt supported and inspired.

Still, I was a long way from mastering my emotions. When I felt cornered, I lashed out. Early in 2017, a fight with a friend came to blows, resulting in a phone call to the police and my arrest. I was charged, to both our astonishment, with a felony offense. I was on house arrest for a month and required to enroll in a 52-week anger management course. At first, I hated it, but my SGI family reminded me that this was my opportunity to transform my anger into happiness.

Chanting proved the perfect time to reflect on what I was learning at anger management classes. Who was I, really, and why? At Buddhist meetings, I watched everyone around me getting along, becoming happy, setting ambitious goals together, and I realized how far from true were certain lessons I’d learned in childhood. Joy—not fear, not anger—is what life is about.

I graduated my ESL program in 2018 and began courses toward an associate degree for transfer and a certificate in clinical medical assistance. Sometimes I felt, with just four years of English, like a toddler. But I found mentors in school and in the men’s division who pushed me. I studied all day, every day, sometimes through the night; I was bone tired. But I held fast to the spirit of my mother’s parting words. I engraved in my heart the encouragement of Ikeda Sensei—“Those who have suffered the most deserve to become the happiest”—and knew my struggles would be worth it.

I also realized that I did not need to be a doctor to uplift another person. One young man had come out to a few of my district’s meetings, then stopped. He was, as I had once been, semihomeless and struggling with his mental health. I texted him quotes from Sensei, chanted with him, met him at the park for basketball—reminding him in any way I could that he was not alone. Reluctantly, he began to trust me and, soon, transform his life with this Buddhist practice, securing stable housing and a job, but most important, a sense of his own worth.

Those who have suffered the most, those who have experienced the greatest sadness, have a right to become the happiest of all.”

Ikeda Sensei (Discussions on Youth, p. 410)

I soon summoned the courage to reapply for the residency documents I had lost in 2016, chanting abundantly ahead of the interview with the immigration officer. Nonetheless, on the ride there, I feared being deported. I watched in quiet amazement, however, as my attorney and the officer spoke like old friends, which, as it happens, they were. The officer was impressed by my efforts in school, work and the SGI community. Beyond the window the sky was overcast. When he told me to expect my green card in a few weeks, a ray of sun broke through, and I thought of my mother.

In 2021, I graduated from College of the Desert with two degrees and highest honors and was accepted to University of California, Berkeley, where I continue to pursue my education in medicine. When I do become a physician, I will go where people struggle the most, as a disciple of Sensei, because these are the people most deserving of happiness.

Today, I understand my anger; I listen to it and express it clearly to others, in a way that opens the door to dialogue. Through Buddhist practice, I have become someone who can listen to and understand myself and others.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles