by Shirley Curtwright

Chicago

In August 1972, I flew in to Los Angeles from Chicago to see my mother one last time. She was in a coma when I arrived and passed away three days later. I buried my mother, my best friend, the morning of the 21st, and that evening, coming back to my girlfriend’s house, where I was staying, her husband mentioned Nichiren Buddhism. I put to him the question I always put to religious people.

“According to you, why is the world so full of good people who suffer and scoundrels getting over like fat rats?”

He thought about this. “In Buddhism, life is eternal. In the ‘book’ of your eternal life, this lifetime is just one page. We can’t know all the causes that the scoundrels and sufferers made in past lives that have destined them to cheat or suffer in this one. However, Buddhism teaches that we can change our karma and our destinies by practicing Buddhism.”

I considered this. My mother, a deeply kind person, had died in the way the women in my family seemed destined to: young, of an illness. While I myself was healthy, it occurred to me that I, too, might soon follow in her footsteps. For years, I’d been batting back suicidal thoughts, an inner voice that said, Shirley, there’s no real win in life. No real reason to stick around. But then I’d think of my mother, of the pain and embarrassment my death would cause her, and I’d push those thoughts aside. Now, with her gone, I sensed how little stood in my way of going through with it. If Buddhism could help me transform in my lifetime the destiny of generations of women in my family, I figured I should at least give it a shot.

As soon as I got back to Chicago, I connected with the local SGI organization and with my chapter’s women’s leader. “I’ll give it my all for a year,” I told her. She took me at my word. For the rest of that year I was in her hip pocket, running around wherever she was, attending meetings, chanting lots of daimoku, studying Buddhism, inviting others to meetings. All of that was fantastic, until she started asking me to take care of the person I had invited.

“What do you mean I’ve got to take care of them?” I asked. “You said, ‘Invite them to a meeting!’ You didn’t say I’d have to take care of them!”

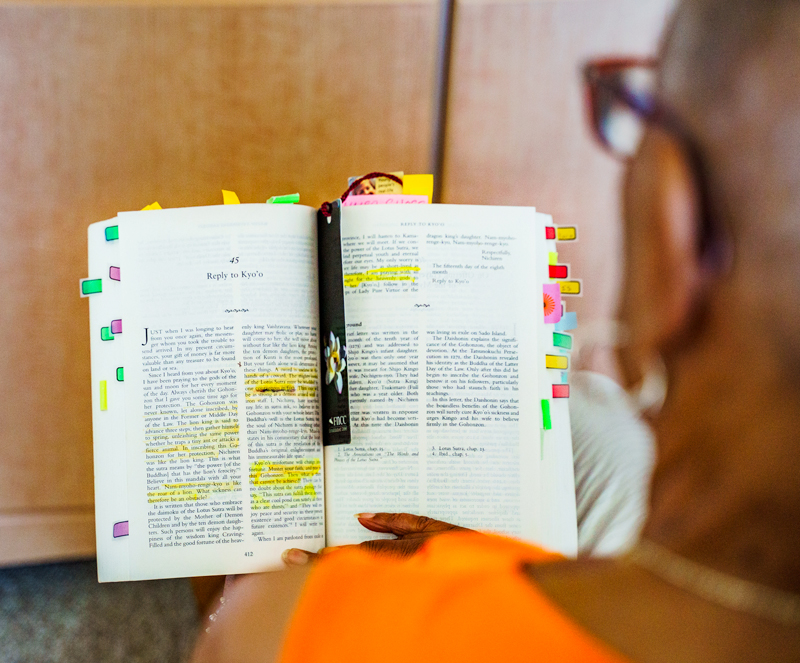

See, I didn’t really understand the mentor-disciple relationship, or why caring for others is at the heart of Buddhist practice. Nevertheless, as I took on responsibility to care for women struggling with similar problems as myself, I found that I understood more deeply the writings of Nichiren Daishonin and the guidance of Ikeda Sensei, not just intellectually but with my life. When someone called with a problem, I’d encourage them, go to them, spontaneously jump up and chant for them. If someone was in the hospital, well, I went to the hospital to see them; whatever was necessary. As I engraved Sensei’s guidance in my life, I began to notice my own tendencies more clearly. The tendency, for instance, to blame or judge others, without reflecting on what I needed to do to help.

Before and after I started my Buddhist practice, I considered myself a compassionate person, someone willing to listen to and consider others’ feelings. And, not to be too hard on myself, basically I was. But deep down, I’d be thinking of the person I was listening to, If only you’d do this or do that, you’d clear your life right up. As I began practicing Buddhism, I realized I was thinking these thoughts in Buddhist terms. Of a young woman struggling with something in her life, I might think: If only you’d keep a consistent morning and evening gongyo! Or, of a family member who was griping on about the same old problems: If only you’d just try this Buddhism!

Changing my destiny … I realized, is no one’s job other than my own.

But as I continued on in my practice, I realized that these thoughts were not compassionate but arrogant. Though I didn’t think I was judging, deep in my life, I was! Instead of taking responsibility, reflecting deeply, chanting daimoku to bring out from my own life the wisdom that I needed to help the person I was talking to, I was essentially telling myself, Well, you can only do so much for another person. As I began to dig, to chant daimoku with all-embracing compassion, I began to experience the true meaning of the mentor-disciple relationship: the joy of voluntarily taking on all obstacles to demonstrate the validity of the Buddha’s teaching. Changing my destiny, transforming my life and my environment, I realized, is no one’s job other than my own.

In 1997, at 63 years old, I had a stroke of the kind that ended my aunt’s life at 54. They told me I’d need three weeks to recover, but me, I was walking out in three days. In 2010, I had cancer, the very same that got my mother, but it went away with a small surgery, no chemo necessary. You best believe I had the whole room chanting before the surgery, and anyone so much as walking past the waiting room was hearing about Nam-myoho-renge-kyo.

These days, my prayer is to dedicate my life unconditionally to kosen-rufu, joyfully fulfilling my vow; to not begrudge a moment of it; to be able to plant the seed of Buddhahood in the life of someone who is seeking the Gohonzon—because this practice has been the key to changing my destiny.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles