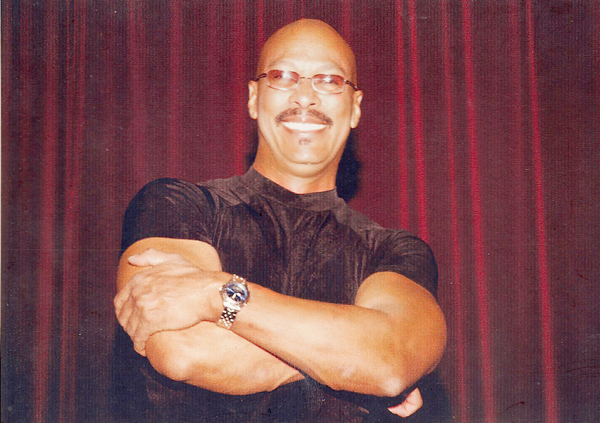

by Johnie Payton

Las Vegas

Just before she died, in 2001, my mother asked me not to hate my father; without him she would not have chanted so much daimoku or changed her karma so deeply. Her hand disappeared into my own, and I gave it a careful squeeze. Her question didn’t surprise me. My father, 12 years deceased, had died in prison for his behavior. He was the first bully I ever met, the first to make me sick with hatred. Without him, I would not have put on 50 pounds of gym-built, steroid-assisted muscle to send a message to him and all the bullies of the earth: Don’t mess with me and those I love.

As a child, the mere sight of bullying made me literally sick, filling me with rage lasting days on end, followed by a cold, a stomach bug or the flu. This happened less and less as I grew older and bigger. Probably because I simply saw fewer bullies to enrage me; if any were around, my presence told them to behave. Also, as I became more active in the SGI, I found myself surrounded by positive, upbeat young people. Joining the Brass Band at 12, I found that drumming vented my energy in a joyful, creative direction. And yet, even as I surrounded myself with positive energy, even as bullies vacated my line of sight, I continued to pump iron at the gym, never satisfied with the results I saw in the mirror. More and more, my workouts became about appearances, fueled by a bullying inner voice that was never, ever satisfied.

Over the years of my Buddhist practice, I’ve received all kinds of benefits; the best wife in the world, a successful music career, a giant drum kit in a dedicated loft so big it makes the drums look small. I also eased off a bit on my workouts. Spending so much time with SGI members, I began to recognize, if slowly, that the people around me didn’t give a damn about what I looked like; they cared about what kind of person I was. All these were wonderful benefits of my Buddhist practice, but they are all completely unlike the one I received most recently. This was not a conspicuous benefit like a wonderful partner, but a benefit won in a do-or-die struggle against an illness that stumped all the doctors money could buy.

In July 2021, I began experiencing severe nausea 24 hours a day, seven days a week. I could hardly eat or sleep. The doctors did bloodwork, ultrasounds, X-rays, CT scans. They tested my gut, grilled me on my diet, did whatever they could think of, but were never able to diagnose it. Within months they grew alarmed—I’d gone from 170 to 130 pounds. All the muscle I’d built and maintained over the years, that I had once relied on to reassure myself and those around me—it was gone. In a matter of months, I’d withered to skin and bones. In October, the alarm on my doctor’s face told me I was justified in fearing for my life.

For a while, I found I couldn’t even bring myself to join an SGI meeting, not even over Zoom. Eventually, though, I realized that this was a battle with the devil king, the most insidious of devilish functions; I could not allow myself to be defeated. I began supporting meetings once again and found that I felt uplifted each time I went. I’ve always chanted abundant daimoku, but battling this illness, I doubled, even tripled it, studying Ikeda Sensei’s guidance as I never had. One that stood out to me reads, “Ultimately, you can depend only on yourself” (The New Human Revolution, vol. 2, revised edition, p. 266).

Taking this guidance to heart, I did just this, putting all my faith in the Gohonzon to activate the healing capacity of every cell in my body, every fiber of my being. If I resigned myself to illness, I was sure there wasn’t a doctor on earth who could cure me. With the spirit to depend on myself, I chanted vigorous daimoku and went into every doctor’s appointment burning with a vow to take even a small step toward my health.

There were days the whole world appeared to me as a place of punishment, a personal hell. And yet, I refused to accept it as such. Chanting, I perceived that this illness was my Buddha nature trying to send a message. There was something I needed to see in my life, something I needed to understand. Little by little, understanding did come. Studying Sensei’s guidance and the writings of Nichiren Daishonin, I began to understand the meaning of the pronouncement: “It is the heart that is important” (“The Strategy of the Lotus Sutra,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 1000).

Slowly, my health began to improve and this January, my weight stabilized. With great joy and enthusiasm, I began to lend my full support to SGI meetings again as a vice region men’s leader. At our weekly Buddhism 101 meeting, I met a woman who was in a life-or-death battle with illness. I told her about my own experience of winning in the face of death and encouraged her to fight like the dickens and turn winter into spring. She did and is winning. I asked her to please share her experience with others going through something similar.

This past March, when the worst of the nausea subsided at last, I had a realization while chanting: I chose this illness, just like I chose my father; neither was inflicted on me.

I felt my hatred for my father leaving my life. And with it, self-hatred I hadn’t even realized was in me: hatred for having once been too small to protect myself and my mother, for being not physically “enough” to help those I love.

I am enough! I am a Buddha with a heart that can move other hearts! This was the deeper message, the hidden benefit, of my illness.

I thought of my mentor then, a man who truly loves people. Because he loves them, he shows them how to fight and win in life’s most fundamental battles, the ones that cannot be won with brawn but only with the heart of a lion king.

What advice would you give the youth?

It’s a given: Difficult things will happen in life. The most important thing is to never give up. No matter what hit me, I stuck with the SGI, and because I stuck with the SGI, I kept practicing, kept studying. Day by day, year after year, I built up all kinds of fortune. But my greatest benefit is that I can now encourage others with my own experiences of never giving up. That’s true happiness right there: helping others.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles