Living Buddhism: Hello, Margaret! We understand you’ve been working at Soka University of America (SUA) for over two decades now. What is the most fulfilling aspect of your work?

Margaret Kasahara: I’m so happy to speak with you. I work as an associate director in the Office of International Student Services. It is my greatest joy and honor to support students from all over the world. SUA offers an extraordinary learning environment and community, with students from diverse backgrounds studying together and bringing their life experiences into rich discussions inside and outside of the classroom.

SUA is a very intimate campus, where students and faculty get to know each other on a level that is not possible in most universities. For instance, I did my undergraduate studies in New York at a university with a student enrollment exceeding 50,000—a wonderful experience, but my teachers rarely knew my name. There’s no denying the sharp contrast in student-teacher relationships developed at SUA, where students and staff know, not just each other’s names, but each other’s stories—where you have class sizes ranging from 8 to 12 students. In my work, too, I’m able to engage in real dialogues, build genuine relationships with other staff, faculty and students. I truly feel this was what Ikeda Sensei envisioned when he began developing Soka schools around the world.

Helping students fulfill their dreams while contributing to Sensei’s dream—to foster a steady stream of global citizens committed to living a contributive life—this has been my deep pride and joy. For me, there is no better way to live as a disciple!

Helping students fulfill their dreams while contributing to the great dream of Ikeda Sensei … this has been my deep pride and joy.

Soka education is also about creating value from any situation. Tell us about how you have done this and how it informs your work.

Margaret: That’s true. The heart of Soka education is not textbook knowledge but a disposition to life—a resolve and conviction that value can be created from any situation. While I attended an academically rigorous high school, my father was always reminding me: “It is the heart that is important” (“The Strategy of the Lotus Sutra,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 1000). These lionlike words of Nichiren Daishonin were perhaps his favorite. They were words I needed to hear as a young person.

On my long daily commute to high school, consisting of riding two trains and a bus, I studied nonstop to keep up with my classmates. In addition to academic performance, material wealth was important to my classmates, most of whom came from wealthy families. My family came from humble circumstances, so I couldn’t help but to compare myself. Moreover, I attended a Japanese language school on Saturdays and because I was the only American in a class full of kids from Japan with Japanese names and who spoke it fluently when I could not, it made me the target of bullying. My parents’ fighting spirit, summarized by Nichiren’s cry, “It’s the heart that is important!” kept me grounded. I remember wanting to throw in the towel so many times, to give up on school, on faith, on so many things, but my SGI friends always brought me back to Buddhist practice and Sensei’s guidance, directing me to my own inherent value. For instance, instead of getting down on myself about getting bullied and excluded, I used my recesses and breaks to read in the library.

Sensei often mentions reading good books in his writings, especially to future division members. I made it my personal determination to read the books that Sensei mentioned; this was how I developed a love for the classics. Some of my favorites included Pride and Prejudice, The Count of Monte Cristo, Jane Eyre and A Tale of Two Cities. The majority of these I read in English. But then, having done so, I began searching out their Japanese translations. Based on my previous knowledge of the stories, I tried my best to follow the plot. This became easier over time, and my Japanese improved by leaps and bounds, eventually enabling me to attend graduate school in Japan and even work as a translator and interpreter at the SGI Headquarters in Tokyo. Engaging with the classics under Sensei’s instruction was, I think, deeply formative to me at this time. Sensei says the following about my favorite classic, The Count of Monte Cristo:

The name Count of Monte Cristo is synonymous with a person of courage, fortitude, conviction and perseverance. People with such qualities make kosen-rufu possible. That’s why we must never retreat in the face of difficulties, no matter how daunting, but keep moving forward with tenacity and determination until we achieve our goal. What blocks our way are self-limiting thoughts—telling ourselves that we’ve done enough, can’t do any more or have reached our limit. But the sun of victory shines when we dispel such thinking, summon forth our inner strength and press on resolutely. (The New Human Revolution, vol. 30, p. 397)

Having struggled at a young age must have helped you overcome challenges later in life.

Margaret: It definitely has. I think the most daunting challenge I’ve ever faced was the untimely passing of my older brother, George. In June 1994, just a few days after I returned home to New York from study abroad in Spain, George graduated from college, but soon after passed away from injuries sustained in an accident. On its own this would have been unbelievably difficult, but it was made all the more so by the Nichiren Shoshu priests who began to slander my parents, who were both longtime SGI leaders, holding up my brother’s death as proof of their “erroneous faith.” All our years of practice as a family came to the fore at this time.

At no point in my childhood can I recall either of my parents complaining about anything or anyone. Whatever they were going through, whatever difficulties we faced, they responded by chanting, studying Buddhism and encouraging SGI members. And in the face of my brother’s death and the slander of the priests, they did as they had always done, only more fervently than ever. I remember that Sensei sent a message to our family to encourage us. He was on a guidance tour of Europe and was no doubt intensely busy, but that didn’t matter; he found the time. This showed me that Sensei and the SGI will be there for you no matter what. I resolved to be this kind of person, who could lend strength to people, to extend my warmth to them even from afar, even when it feels like I’m pushing the limits of my abilities. Through Sensei’s actions, I’m always learning how to live the most noble and expansive life as his disciple.

Not only did we get through this as a family, but we were drawn closer by it. Watching my parents care deeply for the members during this time despite their grief instilled in me the importance of the SGI family. I decided that regardless of what I’m going through I will protect the members no matter what.

Thank you for sharing something so painful. How did this loss affect you?

Margaret: This was a very difficult time for me, so it’s hard to even remember how I got through it. But as a family, we determined that despite this tragic loss, we would create value by becoming people who could empathize more deeply with the sufferings of others. My parents also encouraged my younger brother and me to go to Soka University in Japan (SUA had not yet opened). We both attended Soka with the understanding that we were attending Sensei’s school in my older brother’s stead—so we went with a deep sense of purpose and mission.

What did you learn there that you would bring with you?

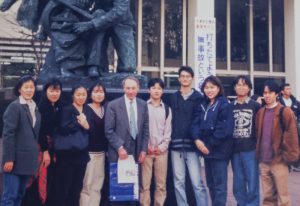

Margaret: I arrived at Soka University in March 1996, just a few months before Sensei would visit cities in the U.S., including New York. In Japan, I was homesick and felt I was missing out on Sensei’s significant trip to the U.S. Shortly after I arrived, however, I was walking with my mother on the campus where we actually ran into Sensei and Mrs. Ikeda! Sensei warmly encouraged us, saying there was no need for regret; I was now at his school, exactly where my mission was. He sensed, too, that my mother would be anxious about the distance between us. He assured my mother that she could go back to New York confident he would care for me while I was attending Soka, just as a father would.

Throughout my time there, Sensei often visited the campus to check in on the students. During our busy exam periods, he would send us meals or snacks to show us he was thinking of us and was cheering us on. Amid his hectic schedule, he was never too busy to encourage us. As people have commented after meeting with Sensei, he truly makes the person in front of him feel like they are the most important person, be they a world leader or a child.

While there, I met young people from all around the world. Sensei spent so much time and effort developing exchanges with other countries. For instance, between Russia and China, at a time when the two were fiercely at odds with each other. I remember waiting in line at a campus food stall, chatting with one student from China and another from Taiwan. I remember one of them commenting, “The two of us talking like this would never happen at home.”

Going to school with people from all over the world, you realize, it’s not so absurd, this simple act of coming together, eating together, talking with one another. No one had to convince me—looking around, I realized beyond a doubt, World peace is possible. And those human connections are, I think, irreplaceable. Turning on the television to hear of a war in a country where you know people is a visceral experience. That war, those people, are not abstract. They are the faces, voices, stories and laughter of people you have met. Feeling this even one time I think helps people understand just how unforgivable war is.

Working at SUA, I try my best to bring Sensei’s warmth to the students I work with. I also fight on their behalf with the awareness that they have an irreplaceable contribution to make here. Through all the ups and downs, I hold fast to my mission as a disciple of Sensei: to fight on behalf of Sensei’s students; to contribute to fostering a steady stream of global citizens committed to world peace.

Thank you so much! Any parting words as the newly appointed SGI-USA West Territory women’s leader?

Margaret: It has never been clearer to me how desperately our hope-filled philosophy of Buddhist humanism is needed to uplift people in our society. I want to strive alongside Sensei to spread seeds of hope and joy everywhere I go and introduce many young people to this practice!

It has never been clearer to me how desperately our hope-filled philosophy of Buddhist humanism is needed to uplift people in our society.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles