The following excerpts are from The World of Nichiren’s Writings, a discussion between Ikeda Sensei and Soka Gakkai study department leaders on the life of Nichiren and context of his writings. They can be found in vol. 1, pp. 2–3.

Katsuji Saito: To begin with, I would like to ask about Nichiren’s writings in general terms.

Daisaku Ikeda: Nichiren’s writings are the Buddhist scripture for the Latter Day of the Law.

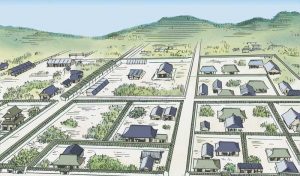

The Great Collection Sutra describes the Latter Day as “an age of conflict when the pure Law will become obscured and lost.” It is a time of extreme confusion among Shakyamuni’s various teachings, a time when they lose their power to lead people to enlightenment. That sutra also describes the Latter Day as an age of unceasing conflict in society. In short, it is a critical time when both Buddhism and society have reached a deadlock and that, if allowed to persist, will likely lead to further confusion and societal collapse.

Nichiren Daishonin saw the Japan of his day as fitting exactly the description of the Latter Day in the sutra. He searched for a way to enable people living in such an age to fundamentally change their lives and realize absolute happiness and, at the same time, transform society. And his discoveries are just as relevant today.

Saito: Of course, his search wasn’t limited to reading.

Ikeda: You’re right. It was a struggle that consumed his entire being.

The Daishonin’s life was a succession of struggles to lead the people of the Latter Day to enlightenment. In his writings, we frequently come across phrases like “Nichiren alone” and “at the beginning of the Latter Day of the Law.” Both express the Daishonin’s profound spirit to shoulder responsibility for everything and to stand in the vanguard of the ten thousand years and more of the Latter Day, to reveal and spread for the first time the great Law that enables all people to tap their highest potential.

Saito: Indeed, his words overflow with his determination as the key figure in the movement to realize true happiness for all.

Ikeda: A host of familiar Buddhist concepts have arisen from Nichiren’s struggle. The “three proofs” is one such example.

Of these, the Daishonin says: “In judging the relative merit of Buddhist doctrines, I, Nichiren, believe that the best standards are those of reason and documentary proof. And even more valuable than reason and documentary proof is the proof of actual fact” (“Three Tripitaka Masters Pray for Rain,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 599). He didn’t only investigate and set forth criteria for determining which Buddhist teaching had the power to lead people to enlightenment. He actively spread that teaching based on those criteria.

Saito: Documentary proof comes from an inquiry into the sutras and other written sources; theoretical proof derives from an evaluation of Buddhist theory; and actual proof means practical verification. The Daishonin pursued all of these.

Ikeda: In other words, he revealed the teaching for the Latter Day by pouring his entire being into his contemplations and actions.

The origin of the so-called five guides for propagation can also be traced to the Daishonin’s steadfast struggle to spread his teaching in the face of persecution. He writes, “One who hopes to propagate the Buddha’s teachings must be aware of the five guides” (WND-2, 259).

As the votary of the Lotus Sutra, he racked his brain more than anyone to uphold these guidelines. Approaching every angle with utmost care, he strove to spread the teaching that would lead the people of the Latter Day to happiness. The standard that he formulated as the five guides is one outcome of this effort.

In short, his writings are a record of his intense struggles over his lifetime. To fulfill his mission, he endured great persecution and left behind a monumental teaching. The collection of his writings crystallizes his spirit, action and instruction. We should therefore read it as the scripture for the Latter Day of the Law.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles