by Heidi Hayashi

Stratford, Conn.

My mother and father were opposites; my mother warm and gentle, my father strict and demanding.

“We’ve given up,” my father would muse, “we might as well be two different kinds of aliens.” But he said this with a little smile. Somehow, though worlds apart, they’d struck on a kind of peace and, baffled by each other, went ahead together nonetheless.

My mother, born and raised in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, had come of age in New York, while my father, the son of a Taiwanese oil painter, immigrated to Japan as a boy with his family after World War II. He graduated university in the states, in Chicago, then moved to Manhattan where he met my mother. When his work called him back to Japan, my blond, green-eyed mother came with him, bringing into my father’s life the Buddhism of the SGI she’d embraced in New York.

Growing up as the daughter of these two people from two different worlds, in a country where I knew no one who looked like me, I was in a constant identity crisis. Who am I? I wondered. Who is Heidi? Though I didn’t have an answer, I knew at least who my father expected me to become. The words he shared most often with me and my brother were, “Get into a top school and top company!”

For my mother’s part, her favorite words were, “Winter always turns to spring” (The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 536).

This passage took on new meaning at age 12, when a medical fluke during a routine procedure robbed my mother of her life. It was like the sun had fallen out of the sky. My father, who’d taken up Buddhism while my mother was alive—somehow agreeing on the point of kosen-rufu when he’d hardly agreed with her on anything else—abruptly stopped practicing and began drinking.

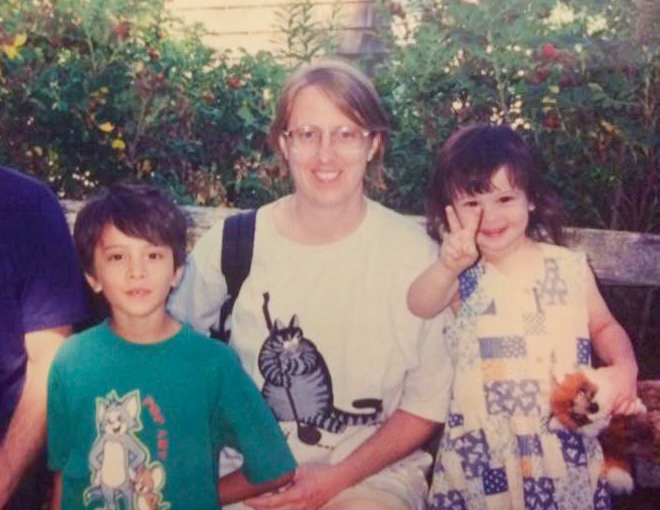

Photo courtesy of Heidi Hayashi.

Her death invited all kinds of hardship into our little apartment. My father was often filled with resentment and rage; the medical lawsuit he filed put us on the financial edge; and he developed a severe health problem requiring open-heart surgery. My paternal grandma moved in to help out; the two of us shared a room until I graduated college. She was deeply opposed to my Buddhist practice, which, thanks to my mother’s friend who visited me every day for months, I took up more seriously.

With everyone around me going through so much hardship, it actually never occurred to me to chant for myself. The least I could do, it seemed to me, was to chant for their happiness and to fulfill their expectations. I did, indeed, graduate from a top university in 2018, and immediately landed a job at a major company. I was the person my father had expected me to become, but it came at a cost I found I couldn’t pay.

As the new employee, whatever work the others didn’t want, they dumped on me. Sleeping only three or four hours a night, I chanted a couple minutes in the morning, just enough to summon the will to get into my business suit and out the door. At the train station, I let the crowd carry me aboard, but as I approached the station near work, I felt I was about to throw up.

When she saw that I could no longer smile, my mother’s friend begged me to seek guidance from a senior in faith.

As soon as we sat down, I burst out: “I’m trying my best!” and then broke down in tears. Actually, I was crying so hard that I couldn’t see the leader’s face. But a kind voice asked: “Heidi, no one would say otherwise. But what are you doing your best for? For what purpose?”

To that, I didn’t have an answer.

At home, I went to the Gohonzon and started from zero, chanting with the open question, “What is my purpose?”

From this prayer came another, quiet at first but then with greater conviction: I want to be a bridge between cultures, to open people’s hearts and bring them together. As my mother had been in her way, I wanted to be a bridge between the people of the U.S. and the people of Japan. Within the year, I left my megacorporation job and moved to the U.S. to live with my aunt in Cape Cod before finding work in New Jersey.

There, I took on chapter leadership and joined the Kayo Core, a young women’s training group. The thing about the core that struck me was the emphasis on personal goals. Eventually, I wrote mine down: Hopefully, I’ll get a job that I love, where I can put my talents to use to bring cultures together.

Hopefully…

One home visit changed my approach. I was visiting a young woman who had a dream she did not believe she could achieve. “You can do it!” I told her. But as I said this, I realized I was stressing the “you.” She heard it, too, I think, and we both had the sense that I was not convinced that I could achieve my own dream. This shook me up. How could I encourage another person if I didn’t believe in myself?

I began to get really serious in front of the Gohonzon about winning for myself as well as for others, which is what Buddhism is really all about. I crossed off the word hopefully in my prayer book; to encourage others, I was absolutely going to score this victory for my life, based on my dream, based on my vow. This was in 2022.

Soon after, a company recruiter reached out with an offer. I’d never heard of the firm, but the job description seemed as though it had been tailor made with me and my dream in mind—I’d even get to travel to and from Japan!

As it happened, the interviewer was Swiss. Upon meeting face to face, I could see he was puzzled, probably wondering, Who is this person, born and raised in Japan, with a Swiss name like Heidi?

“How do you deal with stress?” he asked.

“I like to run and … I practice Buddhism!” I burst out. His eyebrows jumped. He wanted to know more.

I landed the job, and I love it! My uniqueness, I’ve come to realize, is my greatest strength. I don’t have to be somebody else. I’m Heidi! Even in some small way, I’m going to bring people together and encourage them, as my mentor, Ikeda Sensei, has done, winning just as I am.

When we run up against trouble and find ourselves facing adversity, we may think we’ve reached our limit, but actually the more trying the

from Ikeda Sensei (The New Human Revolution, vol. 22, p. 359)

circumstances the closer we actually are to making a breakthrough. The darker the night, the nearer the dawn. Victory in life is decided by that last concentrated burst of energy filled with resolve to win.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles