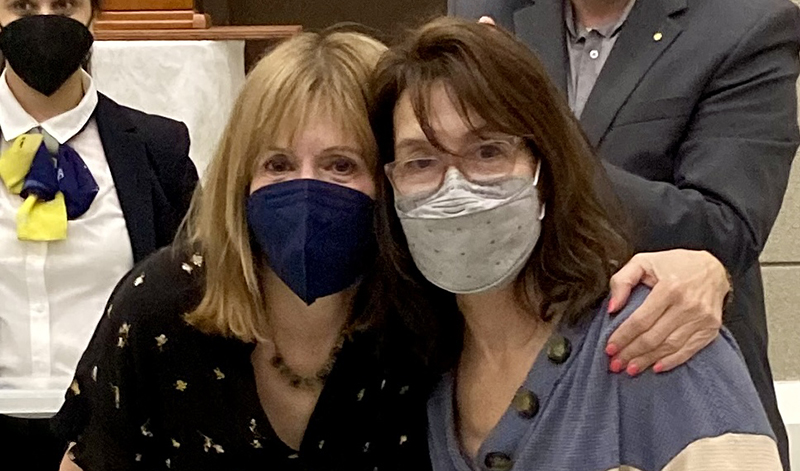

by Sue Wolk

Hempstead, N.Y.

Frankly I was shocked when I heard about the wedding.

“Everyone was shocked,” my childhood friend assured me. “Everywhere, mouths popping open.”

They’d expected a Jewish ceremony, of course—that’s how the bride and most everybody in our hometown of Oceanside, New York, had been raised. But the vows had been Buddhist.

I blanched. How could she? I didn’t mean convert from Judaism; my own family was never particularly observant. No, how could she be mean and a Buddhist?

“Susan’s changed,” my friend implored for the thousandth time. “She really has, Sue; you ought to give her a chance.”

But in my mind, I couldn’t shake it, the feeling, the certainty: Once a bully, always a bully.

Middle school was a nightmare for me; I was different, a hippy, I guess. Come high school, I’d find a whole crowd like me, but in middle school, to be different was a misfortune, something to be pointed out and cured by relentless teasing.

They were a group of five—Susan, their leader—and they all lived on the same block. On the bus to school, they’d all pile in on the corner of Bayfield Blvd. That’s when the torture began.

“Help!” they might sing, “She needs somebody. Help! She needs anybody…”

A Beatles song of all things, gone to waste! They were creative, those girls, taunting me with the songs I loved, scrawling insults on the inside of the bus, inviting me to invented parties at empty homes, or coming over (don’t ask why I’d invite them) to throw my things, one after another, out my bedroom window.

I’d see them over the years, usually at some function at my friend’s. I’d go over in my mind the questions I wanted to pose. But every time, when I walked in the door and heard their laughter, my resolve melted, and I knew I didn’t have the strength to confront them.

I’d neither forgotten nor forgiven what they’d done. Maybe it sounds silly, but I carried resentment and anger for years. It led me to pursue a 40-year career in teaching special education, to uplift and protect children most vulnerable to bullying. And it sent me on a 50-year spiritual quest for answers. Why did you do it? I wanted to know. Why’d you feel the need to be so cruel? The real question, though, was, Why can’t I let it go?

To my mind, a Buddhist was a kind, gentle person. It was impossible to me that the girl, now woman, who’d tortured me could have become what my friend was saying she had. But the news of the Buddhist wedding intrigued me. It might prove to be all fluff, but it did suggest to me that Susan had found a practice she was committed to.

“All right, all right,” I told my friend when she invited me to join them for coffee. “I’ll join, I’ll join.”

The next morning, I walked around the block to my friend’s and knocked on the door. A moment later, Susan opened it. She shouted in delight and embraced me, asking after me and my grandkids. Reluctantly, I had to admit that it was as my friend had said—I could see it, could feel it: Susan had changed.

It was me who brought it up. What was this I’d heard about a Buddhist wedding?

Her eyes lit up and she said it was true; she’d been a Buddhist the past 45 years.

“What about you?” she wanted to know.

What about me? I didn’t know what to call the spiritual practices I’d tried over the years—yoga, meditation, a grand return to Judaism at the age of 50. It was a little of this, a little of that.

“I don’t know, really. But… I am looking for something. What’s Buddhism about?”

I had so many questions but didn’t want to hog the coffee date. We decided to talk again over the phone the following day.

Susan asked if I’d like to try chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. Chanting it over the phone with her, I felt something opening up deep within my life, like something new was being born, like I was setting out on a new beginning.

Susan and I continued to talk, four or five times a week. As we did so, we became quite comfortable with each other, and as we chanted, a new prayer took shape in my heart. I began to chant for the courage to tell Susan how much I’d been hurt by the bullying, how much pain I’d carried with me ever since.

“Sue?” she said, when I told her, “Thank you for telling me this. Not a day goes by that I don’t think about it.”

I must say, that felt so good. Good to know that she hadn’t forgotten, that she thought about it, too. Actually, she looked like she felt better, too—relieved that I’d brought it up at last. At the same time, it didn’t dramatically change anything. The change had already happened in my life and hers: Susan and I were friends. And I sensed—from her and many others in the SGI community—that ours was a friendship that wouldn’t waver.

Since beginning my Buddhist practice, friends and family have remarked on the difference. All my life, I couldn’t stand family gatherings, occasions that left me fuming, closeted up in my room, frustrated by the difference in our political views. Now, I don’t get so bothered. I can listen and, though I may not agree, am able to understand them better. “Sue,” they tell me, “you’ve changed. You used to get so angry.”

Nowadays, I’m always chanting, always studying from the World Tribune and Living Buddhism, always asking questions at our discussion meetings—there’s so much to learn! The Mystic Law, for instance. What is that, exactly?

“You’re always asking about this,” Susan observed one day. We’d studied it many times, but still it felt beyond my grasp. “The Mystic Law is all around,” she continued, “always at work, harmonizing, uplifting life. Right now, for instance, right here—who would have thought we’d meet again? Why have we? And as friends?”

We chant, study and laugh together. And there are times when we actually cry, astonished at how happy we’ve become. We’re going to the SGI-USA Florida Nature and Culture Center together in December, and all of us—Susan, her middle school friends and I—are vacationing together next summer.

I keep a pair of beautiful prayer beads Susan gave me. They are to me a reminder that people can change—people do change—that life is full of new beginnings.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles