What is the sangha?

The Sanskrit word sangha refers to the Buddhist Order, or the community of Buddhist believers who uphold, practice and spread the Buddha’s teachings. This community of believers is the third of the three treasures in Buddhism: the treasure of the Buddha, the treasure of the Law (the Buddha’s teachings) and the treasure of the Buddhist Order. In Sanskrit, these are known as the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. The sangha is considered a treasure because it preserves and transmits the Buddha’s teachings.

At the time of its origin, the Buddhist sangha was characterized by a spirit of equality and consensus that contrasted sharply with India’s caste system, and was not ruled by a small, authoritarian elite. All its members met, discussed and achieved a consensus about the matters under consideration.

In The New Human Revolution, Ikeda Sensei describes the role of the SGI today as according with the original purpose of the sangha. He writes: “Historically, the role of priests is to concentrate on sharing Buddhism with others, fighting against the three powerful enemies[1] and engaging in kosen-rufu. The role of lay believers, in contrast, is to focus on chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, making offerings and speaking to others about Buddhism to the best of their ability … In light of these definitions of the roles of the clergy and laity, today the Soka Gakkai is carrying out the functions of both” (vol. 4, pp. 160–61).

What is the origin of the word “sangha”?

The original Sanskrit word sangha was transliterated as a Chinese compound of two characters to express the pronunciation of the two syllables san and gha. In Chinese society, as the Buddhist order came to be associated primarily with Buddhist monks, the character for san gradually came to be used as a word to mean “a priest” or “monk.” As a result, the treasure of the sangha, especially in China and Japan, came to be understood as the treasure of the priest or priesthood, and more specifically as any individual Buddhist priest.

Nichiren Daishonin, however, throughout his writings, emphasizes the equality of the “four kinds of believers” comprising the Buddhist Order—monks, nuns, lay men and lay women. Yet, in spite of this, the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood capitalized on the traditional, narrower Japanese definition of the term sangha to define any individual priest of its school as more precious and important than any lay practitioner, regardless of that person’s level of practice, dedication or understanding.

Yet the original meaning of sangha is “group, assembly or convocation.” It is commonly translated into English as “harmonious body of believers” and “harmonious assembly of believers,” which indicates a gathering or assembly of Buddhist practitioners who share a unified goal. The most basic definition of the Buddhist sangha is the gathering of people who practice and spread the teachings (Dharma) of the Buddha.

What is the purpose of the sangha?

Nichiren Daishonin declares: “All disciples and lay supporters of Nichiren should chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo with the spirit of many in body but one in mind, transcending all differences among themselves to become as inseparable as fish and the water in which they swim … When you are so united, even the great desire for widespread propagation can be fulfilled” (“The Heritage of the Ultimate Law of Life,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 217).

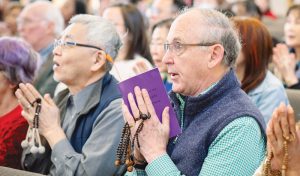

This principle of “many in body, one in mind” captures the prime purpose of the sangha: creating strength from diversity in order to carry out kosen-rufu, the widespread propagation of Buddhism. As a community of Buddhist practitioners comprising countless unique individuals, the sangha is characterized by unity of purpose.

Ikeda Sensei explains that “many in body” expresses the uniqueness of each practitioner’s mission, while “one in mind” means “making [the] great wish of the Buddha one’s own and courageously working for kosen-rufu” (The World of Nichiren Daishonin’s Writings, vol. 1, p. 142).

He further explains that the community of believers maintains harmonious unity in accomplishing the goal of kosen-rufu based on two key elements: the bond of mentor and disciple, and the bond of comrades in faith. And he compares these to the warp and the woof in weaving. The warp, which provides structure in a fabric, represents the bond of mentor and disciple, while the woof, which forms the pattern or design of the fabric, represents the bond of fellow members. “When these are interlaced,” Sensei says, “a splendid brocade of kosen-rufu is created” (The World of Nichiren Daishonin’s Writings, vol. 1, p. 143).

What is the essential spirit of the sangha?

The essential spirit of the sangha is equality. Since its beginning, the sangha pulsed with this spirit of equality (see The Wisdom of the Lotus Sutra, vol. 3, p. 107).

Proclaiming this to be the spirit of Buddhist teachings, Shakyamuni says, “I myself testify to the unsurpassed way, the great vehicle, the Law in which all things are equal” (The Lotus Sutra and Its Opening and Closing Sutras, p. 69). Based on this, Nichiren Daishonin teaches, “Shakyamuni Buddha who attained enlightenment countless kalpas ago, the Lotus Sutra that leads all people to Buddhahood, and we ordinary human beings are in no way different or separate from one another” (“The Heritage of the Ultimate Law of Life,” WND-1, 216).

In contrast, the Nichiren Shoshu priesthood, with which the SGI in the past strove to unite and practice, places emphasis on absolute obedience to the high priest. This goes against the essential spirit of equality in the sangha that Shakyamuni and Nichiren taught. The priesthood’s abuse of its religious authority came to a height in November 1991 when they excommunicated the SGI and its members in an attempt to cause confusion among the community of believers and destroy the SGI. To disrupt the harmonious community of believers is considered one of the gravest offenses a Buddhist can commit.

In the practice of Nichiren Buddhism, the sangha is the harmonious community of Bodhisattvas of the Earth. Ikeda Sensei declares: “Bodhisattvas of the Earth are unhindered by such distinctions as nationality, culture or race. In fact, our global network of Bodhisattvas of the Earth is today forging deep mutual understanding and sympathy transcending differences of ideology and religion. All people are equal, and everyone is worthy of respect. When we awaken to the incredible power that lies within us, we can change our world” (The Heritage of the Ultimate Law of Life: SGI President Ikeda’s Lecture Series, p. 107).

References

- Three powerful enemies: Three types of arrogant people who persecute those who propagate the Lotus Sutra in the evil age after Shakyamuni Buddha’s death, described in the concluding verse section of “Encouraging Devotion,” the 13th chapter of the Lotus Sutra. The Great Teacher Miao-lo of China summarizes them as arrogant lay people, arrogant priests and arrogant false sages. ↩︎

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles