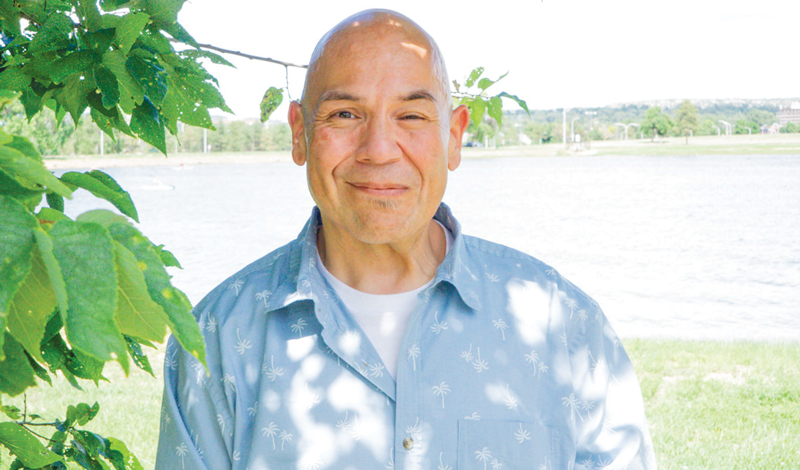

by Steve Salas

Colorado Springs, Colo.

Driving back from a visit to Pueblo, Colorado, last November, I passed an exit I recognized—one that leads toward the home of a friend, a former co-worker with whom I hadn’t spoken in nearly a year.

Bailey, last I’d heard, had bought a home in Pueblo and was living with her fiancé. By the sound of it, she was doing well. No need to call, I thought. But as the low roofs of residential Pueblo gave way to open plains, a stream of faces came to mind—the friends I’d introduced to Buddhism. These were faces I’d been thinking of all week since receiving word of Ikeda Sensei’s passing. Where were they now? I wondered. I couldn’t say.

I owe my life to my Buddhist practice. Admittedly, though, during the pandemic, I’d begun taking much of it—my marriage, home, job, health and friends—for granted.

Nothing was bad, but something was missing. Pondering my mentor’s life, I realized what it was: a deep commitment to others. I always lost touch, I realized, with those I’d helped receive the Gohonzon. In the wake of Sensei’s passing, I made a vow: I will walk the path to happiness with another person, come hell or high water.

On the outskirts of Pueblo, I pulled over, gave Bailey a ring and got her voicemail. I left a reminder that she could call any time. A few days later, she did.

Bailey and I are alike, and I think that’s why we’ve always been open with one another. Independent by nature, neither of us are inclined to confide hardship. Ironically, it was when I’d fancied myself most independent that I wasn’t at all. There was a time when, instead of turning to another person, I’d turned to the bottle. Bailey knew my story, knew that I was nine years sober. And yet, as much as she knew about me, and I about her, I discovered on our phone call that I’d only ever scratched the surface. Things were not only not good, they were critical. Nichiren Daishonin speaks of a “crucial moment.” This was hers, and I was grateful to have prepared for it with intense prayer.

“Remember that chant I told you about?” I asked. “We’re going to do that, all right?”

Every day we chanted, and every other day, we spoke—sometimes an hour, sometimes more. For the first few months, she spoke only in deep pain, only of who’d hurt her and how. In January, I drove down to Pueblo to join her discussion meeting. Appropriately, the discussion topic was on the lowest of the Ten Worlds, the world of hell.

There were women there who had experienced something much like what Bailey was going through. And while she was still going through it, I could tell she was taking in the stories, and also the faces, of these women. They had been through hell, and yet here they were, happy and in healthy relationships.

After that meeting, Bailey and I would keep chanting, keep talking. Day by day, I could hear her life opening up. And every month I drove to Pueblo to join her discussion meeting as her guest.

This April, Bailey received the Gohonzon, an incredibly joyful occasion. In the past, I had considered this the finish line. If a person had the Gohonzon and was connected to their district, I could consider my part done, right? This time was different.

Never had I dug in my heels so deeply as I had pushing off with Bailey on her journey in faith. I realized this time that I’d embarked on a journey of lifelong friendship. Receiving the Gohonzon was just the beginning. I let her know it, too—whatever waves of challenges were waiting on the horizon, we’d overcome them together. And waves, indeed, did come, though the word Bailey prefers is tsunami.

Shortly after receiving the Gohonzon, Bailey was T-boned driving to work, totaling her car and tweaking her back. Her central AC cut out in Pueblo’s unforgiving summer; unexpected expenses depleted her savings; family ties were strained to their limits; she lost her job; and her guinea pig died.

Practically overnight, the trust we’d built crumbled to dust. Why, she wanted to know, are all these terrible things happening to me? I tried to explain the idea of expiating negative karma, to which she replied, “You knew this would happen?”

She stopped chanting. But even then, we kept talking. Again, I found myself listening, mostly, chiming in here and again, reflecting after each call on what had gone well and what I might’ve done better. Importantly, by this time, it wasn’t just me she was talking to.

Refusing to chant, in the depths of depression, she was nonetheless willing to hear from the women in her district. Together, we did our best to support her.

There was no way I could have seen Bailey through all that on my own. The women in her district were key. As much determination as I brought to Pueblo each month, I took back double to Colorado Springs. Watching Bailey transform her life revitalized me, too. The spirit to leave no one behind is one our friendship engraved deep within my life. I began reconnecting with those I’d introduced to Buddhism but had lost touch with, and also with members I hadn’t seen in a while.

This September, Front Range Chapter will welcome three new members to our Soka family. Deep friendship lies at the heart of each person’s decision to receive the Gohonzon.

Looking around me, I can say that the spirit of friendship has taken hold in Front Range Chapter. This is where the promise to leave no one behind, come hell or high water, lives and breathes.

Bailey Wilhelmi: It was sometime in May, when my circumstances hadn’t yet changed, when my life was as hard or harder than it had ever been, that I realized something. In the past, ‘Gosh, best of luck,’ was the best encouragement I could expect from friends and family. But this time, the friends I’d made in the SGI were convinced I would win, were determined that I would, were certain that on the other side of my suffering was my happiness. I didn’t have to do this all alone. I started chanting again, a little at first, and then more each day. And one after another, rays of light broke the clouds overhead.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles