Living Buddhism: Thank you, Akiko and Lee, for sitting down with us today. Akiko, you began your Buddhist practice in late-’50s Japan, a country in recovery from war. How did you begin your practice and what was it like?

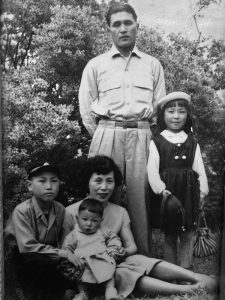

Akiko Look: Thank you so much. In a sense, it was my father’s fascination with mahjong—the ancient tile game of strategy and luck—that brought my family to the Gohonzon. Specifically, his habit of gambling all he had on this, his favorite game.

My mother, a Taisho-era woman, kept her deep misgivings to herself. Now and again, though, she’d be heard, venting softly to herself, just the one word, again and again: “Mahjong!”

By the time I was born my father had racked up debts he couldn’t possibly pay, totaling, my mother swore, the value of three homes. Ironically, growing up, we had many—more homes than I can count—moving place to place, running from debtors.

Twice my mother attempted to take her own life and still my father played mahjong. Just once, when I was 12, I asked him why he did it.

“Playing mahjong,” he said, his eyes suddenly old and sad, “I feel like I felt on the mound.”

The pitcher’s mound? Your father was a baseball player.

Akiko: He was. Or rather, he had been. He injured his shoulder soon after I was born, and after that left the sport forever. If I ever saw him play, I don’t remember, but others did. They remembered my father the baseball player, not the gambler.

When did he join the Soka Gakkai?

Akiko: In 1959. I was 13. His former baseball coach introduced our whole family to this Buddhism, but it was my mother and I who really took to it.

What did you think?

Akiko: About the Soka Gakkai? To be honest, much of what was said of it back then was true—we were, many of us, poor, without education, sick. From that description alone you’d think we were an unhappy bunch. Not so. In a country where people rarely looked each other in the eye, where even among family, it was not uncommon to keep suffering a private affair, there was an openness and vitality among the people of the Soka Gakkai.

At 15, on November 12, 1961, I joined the historic Ninth Young Women’s Division General Meeting, where 85,000 young women gathered at Mitsuzawa Stadium in Yokohama, Japan. Suspended above the stands, a huge banner shared the theme for the coming year: Victory!

Ikeda Sensei took the stage. “What is the purpose of faith?” he asked. “It is nothing other than to attain Buddhahood. Or, more simply … to develop a state of absolute happiness that nothing can destroy.”

At this meeting he gave the young women an eternal guideline to base our lives on study so we could declare with pride: “No one knows more about Buddhism than we do. Let us teach you about it!”

In closing, he expressed his hope that our development alone would dispel the doubts of others—that we would be able to challenge anyone joyfully, saying, “If you want proof, just look at our lives!” I began to chant to live like the sun, shining always, high above the clouds.

That day, in my heart, I made a vow: I will live my life together with you, Sensei!

And your parents?

Akiko: Less and less my mother vented to herself. More and more she spoke her mind. I remember one spirited threat, to have my father’s tomb topped with his own special-made mahjong tile. Playfully said, it actually made my father laugh. Once a woman who hid in the backyard at the mere hint of conflict, her prayers to the Gohonzon gave rise to joy, and joy to strength. She spoke her mind elsewhere, too—with her friends, about Buddhism. And slowly, slowly, my father began to change.

In 1979, to commemorate 20 years since taking faith, we hand-delivered a parcel of Oseki rice (a Japanese dish of sticky white rice with azuki beans served on special occasions) to my father’s old baseball coach and his wife, who’d introduced our family to the practice. At this point, my father was no longer a gambler and our family no longer in ruin. My father managed a successful business. I remember wrapping them a big heap of this special rice and having leftovers to spare. At this point, we had plenty to give.

And at this point, you and Lee had actually met each other—is that right?

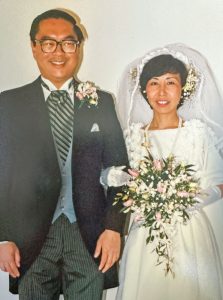

Akiko: That’s right. Some years earlier, in 1973, I’d traveled to San Francisco and stayed there a year with my friend Fumiko. She introduced me to Lee, who struck me as a very warm and sincere person. But I wasn’t looking for a husband at the time. I was enjoying my youth and my freedom, working as a travel agent in Ginza. Ten years later, however, I traveled to San Francisco again, once again at the invitation of Fumiko. She kind of set us up, Lee and I. My brother had come with me this time around and told me, rather pointedly, after meeting Lee: “He is a really kind person.” Something like a little bell went off in my head. We married the following year.

Lee, you encountered Buddhism in the U.S. in the late ’60s, as the country was preparing for war. Tell us how you began your practice.

Lee Look: I was a student, and like many young men at the time, I did not see the value of going to war. I was introduced to the SGI on my college campus and was open about what I’d be chanting for: to stay out of the Vietnam War. Hawaiian by birth, I resonated deeply with the spirit of family I found in the SGI. I vowed to the Gohonzon that, should I escape the fate of war, I’d devote myself fully to the cause of peace, as someone who could protect the people.

Draft exemptions were reserved mostly for the ill or physically impaired.

Lee: I sought out three opinions, three doctors. The first found nothing wrong with me and the second, too. The third, though, was an eye specialist, a retinal surgeon. Looking me over, he discovered, to his surprise, that both retinas were beginning to detach. It was a stroke of luck, he said, that we’d caught it so early—had we not, I might’ve gone blind in a few years’ time.

They operated on the right eye, then the left, allowing one to recover before beginning operation on the other. All told, the process took over two months, during which time I was recused from the draft. Once recovered, I made good on my vow, getting fully involved in SGI activities.

I learned then and have been reminded since, that when you tackle your problems with prayer, basing yourself on the Gohonzon, you will often resolve not only the problem you’re chanting about but also problems you didn’t even know you had. As Nichiren Daishonin says, “Unseen virtue brings about visible reward” (“The Farther the Source, the Longer the Stream,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 940).

Akiko, your parents come to San Francisco in 1984 to meet Lee and his parents. How does that go?

Akiko: With few words, my parents understood Lee. After meeting on the first night, my parents and I headed back to our hotel. When I saw my father’s tears of joy and sorrow as he sent his only daughter to marry someone 6,000 miles away, I was able to forgive him for all the mistakes he had made. Before he left, he told me, “Having met Lee, I know I have nothing to worry about.”

I shared his confidence. But there would come a time, for reasons that had nothing to do with Lee, that that confidence was shaken.

Tell us what happened.

Akiko: It began with a simple decision—Lee decided to leave his job, the one he’d had for years. We were living in Albany, California, about a 30-minute commute from San Francisco by train. His company changed locations, to a spot a few miles off the BART line. Lee, who took the train, decided to search for work he could walk to from the train. Our kids, Akira and Yumi, were 6 and 3 years old. I didn’t think much of it—I figured he’d land work before long and we’d be all right. But to our shock, we discovered that Lee’s work, the work he’d done for the past 17 years for his company, was no longer in demand anywhere else.

How could that be?

Lee: It sounds strange, I know. I ought to say something here about my work, which is in the field of cyber security. In the early days of the trade, when the internet was young, I studied and mastered a particular program, in popular use at the time. Over the years, however, unbeknownst to me, my program was losing relevance. By the time I quit, it was in use by very few companies. What this meant, I discovered in the following years, was that there was very low—almost nonexistent—demand for my skillset anywhere in the country. I was fortunate early on, to find work, landing a job in Burbank, California, in 2001. I went to Burbank and they stayed in Albany. The job, however, was over before the year was out; they were switching to a new security service. I packed my bags and hit the road. I called Akiko on my way home.

Akiko: “Coming back?” I asked. I was happy to see him sooner than expected, but sensed something else coming toward me, too, something that felt beyond my control. My karma, I thought.

What did you fear, exactly?

Akiko: Simple, day-to-day things. That we wouldn’t be able to put food on the table. That we’d lose the house and have to move from place to place. In short, I feared to see my children live some version of my childhood, their friendships cut short before they’d been given a chance to grow. While Lee was still on the road from Burbank, I called my friend Fumiko, who’d introduced us, and told her what had happened.

“This is your chance to change this karma,” she told me. I sat down and began to chant. Fears and worries flew threw my head—of all the worst-case scenarios that could unfold for us. But from among these, other ideas began to occur—the hopes Lee and I shared for ourselves and our children. Burbank is a 370-mile drive to Albany. By the time Lee was home, these hopes had given rise to a determination.

“What do you say?” I asked him. Without hesitation, he agreed: For the next 10 years, we would double our May contribution and send both our children to Soka University of America (SUA).

Wow. What followed?

Lee: As mentioned, work in my field was hard to come by. The upside was that I had plenty of time. Every day for the better part of a year, Akiko and I chanted many hours together toward finding a job that would put food on the table, pay the bills, allow us to hit our contribution goals and send our kids to SUA. Before the year was up, I’d found a job—a year’s contract in San Francisco. Once that was up, however, the battle to find work began again. And so began 10 years of moving place to place, taking jobs in San Francisco, Phoenix, Oakland, Dallas and South Dakota. The best contracts lasted about a year, and there were gaps between them. Over this time, we refinanced the house four separate times, increasing our mortgage, but always putting food on the table, always saving up for our children’s educations and hitting each year our contribution goal. Wherever I went, I plugged in right away to the local SGI, my home away from home. I was never without the sense of Ohana, of family, and it gave me the strength to fight for my family’s protection at home.

Akiko: I visited him once, in the middle of his contract in South Dakota, in 2011. By this time, our son had graduated SUA and our daughter was in her final year. Lee, I knew, had been working out of a motel, but he had not mentioned its size. When I saw the space—no larger than four tatami mats—in which he slept and lived and worked long hours day after day, I got emotional. I realized just how much he was fighting so that me and the kids could live without worries.

When did this work saga come to an end?

Lee: In 2013, when I landed a job in New York.

New York?

Lee: Remotely! An incredible job at a large bank that I do from home. It allows me to utilize all of my past experiences and pays a higher salary than any of my previous work. These days, I try not to take it for granted—I get up and take my time with my morning routine: gongyo, then breakfast, then I wash and get to work. At the end of the day, I have a home-cooked meal with Akiko. The thing I missed the most, though, was building community, deeply knowing my neighbors and the members in my district and chanting hard for their happiness. That’s what I’m enjoying most these days.

Right on. Akiko, what are you up to?

Akiko: For years, I dreamed of going to school. In 2017, I enrolled in a correspondence program at Soka University, in Hachioji, Tokyo, receiving my bachelor’s in education in 2021. Then, upon graduation, I enrolled for a second bachelor’s in literature, which I completed last year. I can say that I have walked the path of lifelong learning, and know that at the end of my journey, I’ll be able to say with pride that I kept my vow, the one I made so many years ago in Mitsuzawa Stadium: I’ve lived my life together with you, Sensei!

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles