Living Buddhism: Sharif Fennell, father of three, award-winning neurosurgeon, former University of Massachusetts football team captain… We can forgive the onlooker who credits destiny for such a résumé. But you were not, as the saying goes, “Born to it.” Your achievements did not come easy.

Sharif Fennell: No, they did not. In fact, I was once deeply reluctant to even speak my dreams aloud. One notable occasion was with my high school football coach. I told him I wanted to play football at a Division I school, and he laughed. “You’d be lucky to clean the showers at a DI school.”

That sounds harsh. He was referring to your athletic performance?

Sharif: Athletic, academic—all of it. At this time in my life, I did enough to get by, and not always even that. Part of it, I think, was wanting to fit in—not wanting to stand out in any way, good or bad. It was morphologically impossible for me: I was quite tall, lanky, one of 20 some Black students at predominately white Melrose High, a school with a student body of 3,000. Any class I walked into, it was a near guarantee that I’d be the only kid who was Black.

But that summer, something shifted in me. I hit the gym and the books, putting in the work required to stand a chance of playing DI. I reenrolled in the courses I’d done poorly in and aced them. I discovered that I could stick out in a good way, that I could be an inspiration to my classmates.

All that sparked by your coach’s comment?

Sharif: Oh no. In fact, I’d say I pushed myself in spite of that comment, not because of it. My driving force was my mom, whose driving force was her Buddhist faith. I mentioned that I was reluctant to share my ambitions with anyone, but that’s not entirely true. She was the exception. I shared them with her, and crucially, she believed in me. Early on, she identified what has been my life’s greatest enemy: fear.

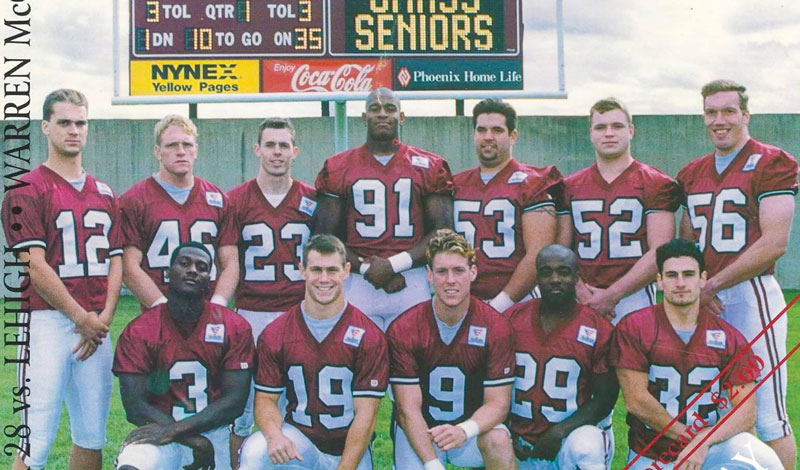

In 1992, you entered the University of Massachusetts on scholarship?

Sharif: I was accepted, but not on scholarship. Still, I arrived two weeks early, with the other football recruits, as a walk-on. The coaches hardly knew who I was. Physically and academically, the recruits—highly sought after athletes from Louisiana, Georgia, Ohio and Texas—far outstripped me in every respect.

Any ounce of confidence I had at this time was drawn from my Buddhist practice. Even this, however—relying on my faith—was difficult to do, given that I was bent on hiding it from everyone.

Why hide your practice—and how? You must’ve had roommates?

Sharif: Seven of them. Eight in all and one bathroom between us. And that’s where I chanted, intensely, quietly, an hour in the morning and an hour at night. Frankly, I can’t imagine what my roommates thought of this—at the very least that I was astonishingly inconsiderate. As to why, I think it goes back to fear—in particular, a fear of sticking out. I’d never once spoken to my peers about my Buddhist practice. It never even occurred to me to add to our differences. The whole roommate situation, however, was what did push me in the end. That, with the help of my mom.

She rang one evening, on the shared dorm phone while I was doing gongyo. One of my roommates answered and made some exasperated remark—I was approaching the half-hour mark of bathroom time. They banged on the door: “It’s your mom.”

She asked me to explain myself. I did and was met with a stream of strict guidance.

“You’ve got to tell them who you are,” she told me. “You cannot slander your practice like this, hiding yourself from the world. And don’t let anyone else slander your faith either. You tell them what you’ve been doing in there, else who knows what they’ll think.”

I took a deep breath, hung up the phone and turned to face my roommates. I’d been carrying around an outsized fear of this particular conversation, one I’d envisioned as a kind of interrogation, each roommate firing off doctrinal questions that I didn’t have answers to.

But their questions, as it happened, were frank.

They wanted to know the meaning of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo; my reason for chanting; what I thought happens when we die; and what it means to be Buddhist. I told them that chanting helps me identify and focus on the concrete actions I can take day-to-day to become the best version of myself. This conversation, this coming out of the bathroom, if you will, was liberating. Away from home, facing this fear head-on for the first time, is when I began to truly own my Buddhist practice as an indispensable part of the person I presented to the world.

This opened inner doors to myself, to new reserves of energy and confidence.

That year, I really came into my own. I secured a full ride—my tuition paid with athletic and academic scholarships. By senior year, I was team captain, at which point my high school coach invited me to speak to his current crop of athletes about the spirit to give your all and to never give up on a dream. When I graduated, I did so with the highest honors.

What happened after college?

Sharif: I knew by then that I wanted to be a doctor. It seemed to me the best way I could take care of people and make a positive impact on my community. I enrolled in a few qualifying courses and by 2000 was studying for the MCAT, a test that proved far harder than I’d anticipated.

Multiple times, I scored poorly. Despite this, I was, rather arrogantly, sending applications to the top medical schools around the country, getting rejected by all of them. Each low test score and each rejection letter made me question whether I was on the right path, whether I was cut out for the job. I was a young men’s leader in the SGI, fighting on the frontlines of our movement—why wasn’t I seeing concrete progress?

Visiting a future division member, I asked him what his dream was, to which he simply shrugged and turned it back on me. “What’s yours?” he asked. I told him. “Well,” he said, “what are you doing about it?”

The question stung. But then I thought, You know, he’s kind of right. I’d been telling myself that I’d been giving my all, but that wasn’t true. I’d been doing enough to get by while justifying my lack of progress.

In 2003, after underperforming yet again on the MCAT, I attended a conference at the SGI-USA Florida Nature and Culture Center, where I sought faith guidance. I hadn’t broken through, I told them. Why not? I got another answer back in turn: What did I think it meant to bet my life on achieving a dream?

Chanting about this, I realized that my prayer had been focused on a fairly superficial goal: showing actual proof by getting into a top institution. Was this my dream, though? Is that where it ended? Even if I got in, there was no guarantee that that institution would make me into a great human being. Asking myself what Ikeda Sensei would do in my shoes, I realized that he certainly wouldn’t wait to be validated in the eyes of the world. I decided to respond to my mentor, now, not later, as I was, right where I was.

What did you do?

Sharif: I began to visit as many young men as possible. I remember a core of five—all of us piling into one car to visit the young men in the area. One I recall clearly, and not because we saw him often. He lived in New Hampshire, over an hour’s drive. He’d talk and leave no room for conversation, slandering himself and others. We all fought the urge to interrupt him, to dispute, to defend him from himself. We just listened.

We’d chant a lot before these visits—on the car ride, too. I don’t think it occurred to any of us at any point to avoid him. It would have been easy—his house was out of the way, there was little indication that our visits were appreciated. He’d have withdrawn and, in all likelihood, not be seen or heard from again.

But we kept going. Eventually, his monologues grew less spiteful, and shorter. Soon, they’d quieted down, and we were able to speak with him as equals. He began coming out to meetings, which astonished everyone, and then he shocked us again when he started supporting activities behind the scenes. The spirit to leave no one behind, to take on the sufferings of others as one’s own—these I truly engrained in my life at this time.

While an MCAT score tells you nothing about the quality of a person’s character, my vow was reflected in everything I did, the MCAT included. I had awakened to my vow—not as a Buddhist aspiring to become a doctor but as a Bodhisattva of the Earth carrying out his mission in this lifetime to remove suffering and impart joy in all areas of life. Of course, if I wanted to become an example for others to follow, I also had to win. I had to rise to the top of my field and serve humanity. This is Sensei’s guidance to young people.

Med students take an oath—the Hippocratic Oath—upon induction. Nonetheless, even among those with such a text as their ethical foundation, your behavior stood out. Upon graduating, you received an award for humanism—the Georgetown Star—normally reserved for faculty. And this was followed soon after by the Arnold P. Gold Foundation Humanism in Medicine Award.

Sharif: Yes. The dean of Georgetown, upon conferring the star, remarked that he could not recall another instance when the award had been given to a student. I mention this only to highlight the training I received in the SGI, with its emphasis on respecting others and standing with them.

You went on to complete nine years of training, including a six-year residency at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Something happened there in your second year. Tell us about that.

Sharif: We got a call—there’d been a shooting outside a nearby grocery store where Arizona State representatives were meeting face-to-face with their constituents. Congress on Your Corner, it was called. One constituent who came was a deeply disturbed young man. He was armed. He shot several people, including a U.S. representative in the head at point-blank range. I was the first neurosurgeon there when the news came in. Though in my second year of residency, I understood immediately that I’d be one of the surgeons performing this life-or-death surgery.

That story shocked the country at the time.

Sharif: It shocked me. You mentioned the spirit of the Hippocratic Oath. You’re absolutely right that it’s a profoundly ethical document. Even so, it’s not uncommon for medical professionals to distance themselves from their patients—it’s actually a very human reflex, to protect oneself from suffering. Those who do this are trying to protect their humanity, but ultimately, I’ve found that you cannot distance yourself from the humanity of others without distancing yourself from your own. Because I’m a Buddhist, because I can refresh myself in front of the Gohonzon, I’m able to take on the sufferings of others without being crushed by them, without becoming a cynic. In fact, doing so, I feel, is what allows me to be fully human.

I performed the operation on the member of Congress, praying for the peace of the land. Late into the night, between the different phases of her care, I spoke with her husband. Those conversations, as difficult as the circumstances were, remain a cherished memory. Her survival was itself considered a miracle by the press, but she did more than survive. A year later, she hugged me, thanking me warmly. She went on to work avidly for causes near and dear to her.

Your life has not slowed down since completing residency, in 2016. You’re a father of three, teach, operate and diagnose. What’s a day in the life?

Sharif: Life has certainly not slowed down. I’m usually up by 5 a.m., 6 at the latest. If I’m not scheduled for an operation, I have teaching conferences in the morning, followed by surgical cases around 7:30 or 8 a.m. or outpatient clinic at 9 a.m. I then start seeing patients in 15-minute increments, averaging 25 to 30 such meetings in a day. The day wraps by prepping for the following day.

What is your prayer going into a day like that?

Sharif: To make each person feel understood and heard, and impart hope.

How do you do that with 15 minutes?

Sharif: Honestly, I leave that up to the Gohonzon—it’s all life condition, all daimoku, all the spirit to respond to my mentor. An old friend of mine referred me recently to Sensei’s 2012 peace proposal, which returns repeatedly to the idea that at the core of Buddhism is the spirit to share the sufferings of others and advance together with them. That is what I intend to do until the end of my life, as a doctor, as a father, as a friend and as a Buddhist. This is my vow. Living it, I have nothing to fear.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles