Living Buddhism: Everett, thank you for telling us your story. You come from a long line of educators. But you were determined to break with tradition.

Everett Boyd: I do, I was. My mother, a warmhearted, coolheaded teacher, was not easily ruffled. Two notable exceptions: The first, when I announced, at 16, that I intended to become a musician. “I’ll never do what you do,” I felt the need to add. She worked hard—too hard, I felt. Not the life for me. “You’ll be poor!” she cried, but I didn’t listen. I’d struggle at first, sure, but I was bent on having my name in lights.

The second, in 1987, when she received news of my engagement. The call to her came from my fiancee, Khadija, from her office phone at the Moroccan embassy. “Are you crazy?” my mother fumed. “He doesn’t have any money!”

But we were in love. Over the course of my band’s two-week tour of Morocco, I’d fallen in love with our cultural guide. Whether my proposal was an act of courage or foolishness, I don’t know. What I know for sure is that what followed—married life in New York—demanded many acts of courage.

Poverty, or near-poverty, is almost expected by young, up-and-coming artists in New York, isn’t it?

Everett: Typical for New York musicians, yes. But I’d say the problem of my poverty—

now our poverty—was more than a problem with the city. I’d begun practicing Nichiren Buddhism three years earlier, in North Carolina, and had the great good fortune to have met someone willing to bring the problem bluntly to my attention. “I see you like stuff,” my bass teacher, who was Buddhist, told me. “That’s fine. But true fortune is found among people, in your connections with them.”

When I moved to New York a few years later, I encountered other Buddhist musicians. They put to me a question that I hadn’t given much thought to until then, which was “What are you trying to say with your instrument?” As I studied Nichiren’s writings and the works of Ikeda Sensei with them, I began to get a sense of what it was—the message that Sensei had engraved from his mentor, Josei Toda, and embodied throughout his life:

A great human revolution in just a single individual will help achieve a change in the destiny of a nation and, further, will enable a change in the destiny of all humankind. (The Human Revolution, p. viii)

What did your bass teacher mean by “stuff”?

Everett: He was pointing to my preoccupation with appearances. The saying “out of sight, out of mind” rings especially true for musicians in New York, where keeping up the appearance of success in the music scene can be just as important as actually developing one’s craft. Despite words of caution from many of my Buddhist friends in the music world, I spent enormous amounts of time chasing the appearance of success, until I came up against a bit of news that stopped me in my tracks. Khadija was pregnant.

You didn’t feel ready.

Everett: I wasn’t ready. We weren’t ready. This was in the winter of 1989. Just a few months earlier, I’d been laid off from a part-time teaching job on the West Side. Khadija, too, had just been fired and was filing a lawsuit—her last day of work was the day she told her boss she was pregnant. Needless to say, neither of us was “bringing home the bacon.” Neither had insurance. Just the two of us, we were barely getting by.

Can I make it here as a musician? Do I have what it takes? These questions swirled constantly in my mind. But now, these doubts quieted down. Or rather, they rearranged themselves into one gigantic doubt: Could I be a father?

I needed guidance. I brought my question to a senior in faith. Frankly, given my situation, I thought he’d ask me, as my mother once had Khadija, if I was out of my mind.

Instead, he reminded me that challenges are opportunities to expand our lives. Whether we practice Buddhism or not, he said, challenges are guaranteed to come our way. Failing to take on those challenges, it’s almost certain that we’ll repeat our mistakes in this lifetime and the next. He asked me to take care of what I had to take care of now. “As a disciple of Sensei,” he said, “you have a great responsibility to become the best person you can possibly become.”

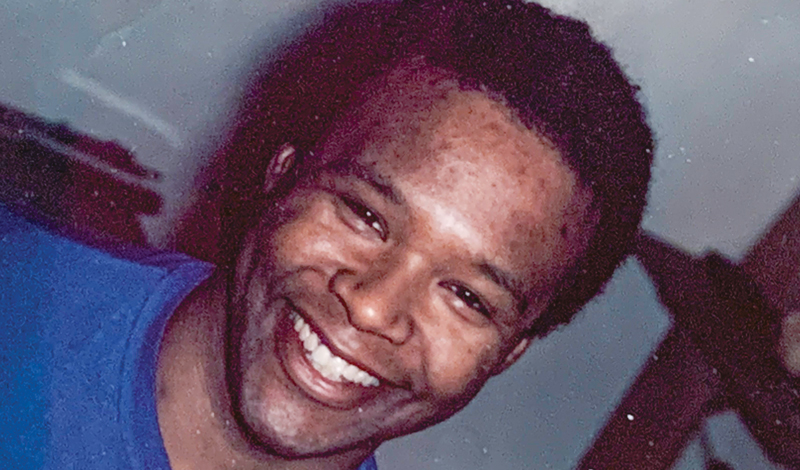

In September 1990, we became parents, welcoming our son, Zach, into the world.

Now there were three of you. What did you do?

Everett: First off, I prayed. I prayed seriously for things I hadn’t been so serious about before, back when it had been just Khadija and me—things like keeping a roof over our heads and food on the table. Though it might sound crazy, it was at this time that I challenged myself to up my sustaining contribution to the SGI-USA. It represented a challenge to myself to bring forth appreciation for everything in my life, hardships included.

A significant shift. What came of it?

Everett: A steady job, for one—hard to come by in New York. I didn’t know where it would come from, but I knew that it would, so long as I continued taking action based on prayer. Soon after Zach was born, a job did come, on the recommendation of my previous boss.

Your previous boss, from the teaching job that had let you go?

Everett: Yes, the same from the program on the West Side. Odd, isn’t it? Why would the person who’d laid me off from one job recommend me for another? She’d let me go because of my tardiness. She was aware that, while there, I’d been hit by a 20-day bout of “walking pneumonia,” a mild pneumonia that nonetheless makes every day a battle. She knew, too, that my commute was long and arduous. And she also knew, despite everything, that I’d cared for the students. She did not know that I’d chanted for them morning and evening, but apparently, it had shown.

In any case, Khadija landed a job of her own at this time, in the financial sector with full benefits. We both felt protected. But I didn’t stay grateful for long.

How’s that?

Everett: I wasn’t ready or willing to give up my dream of stardom. Whenever I saw a former bandmate at a high-profile venue, or heard that another was touring with a well-known band, I’d wonder, Why them and not me? Among my students, too, there were those who went on to receive wide acclaim, and I’d catch myself asking the same question, comparing myself constantly and always feeling I was coming up short.

I’d get off work each day and stay out late into the night, either doing SGI activities or hitting the town. If it was the latter, I’d spend money like water. Our rent was paid late, if at all, and there came a time when Khadija was bleaching dishcloths in the tub, having no money to take them to the wash. She did the same for the white shirts I wore to my Soka Group shifts. At some point, she presented me with a calendar she’d kept of my home attendance. “Ninety days,” she said, flipping through the blocked-out months. “Ninety in a row you’ve been gone!”

Even in dire circumstances, I somehow never missed making financial contributions to the SGI-USA. Sometimes, it was painful. Wasn’t this money the freedom to do as I pleased? To be seen in the crowd I wanted to be seen in? Wasn’t I setting myself back from the life I wanted to live? Each time, I battled with these thoughts, and each time I overcame them. It was a practice, you could say, of overcoming my own pride and selfishness. And it was a practice that saved my marriage.

As things went from bad to worse, as we began to fight and talk of separation, I sat myself in front of the Gohonzon to chant. As I did, my thoughts turned from the pursuit of fame and fortune to what was immediate and essential: my family, my work and my faith. I wanted us to advance as a family, not just scrape by on my own. I wanted to say something—not just with my instrument but with my life. And I wanted to say it to the people I’d been taking for granted, the ones who supported me most. Nichiren Daishonin was adamant that Buddhism shines only through our behavior as human beings. To a disciple he writes:

Live so that all the people of Kamakura will say in your praise that Nakatsukasa Saburo Saemon-no-jo is diligent in the service of his lord, in the service of Buddhism, and in his concern for other people. More valuable than treasures in a storehouse are the treasures of the body, and the treasures of the heart are the most valuable of all. From the time you read this letter on, strive to accumulate the treasures of the heart! (“The Three Kinds of Treasure,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 851)

Basing everything on prayer, I told Khadija that I wanted to purchase an apartment in Brooklyn.

She took this in with a deep breath. “I grew up poor,” she reminded me. “I know what to do with money. If we’re going to pull this off—really pull this off—then you bring me the paychecks and I’ll handle the money.”

This pricked my pride and set off an uproar of indignant thoughts. But I didn’t storm off or blame or refuse. This was bigger than me, and it included me, too—it was about my wife, our son, our future.

I cut back on spending and focused seriously on the essentials. I advanced in every area of my life—as a teacher, musician, husband and son. My parents sensed the shift taking place in my life. I had begun appreciating them, too, and expressing it in words and actions. With their support, Khadija and I did the impossible, purchasing our own Brooklyn apartment in 1992.

Did others notice as well?

Everett: They did. In 1996, I was asked to teach at a K–8 school with a mission “to foster educated, responsible, humanistic young leaders who will through their own personal growth spark a renaissance in New York,” based on the conviction “that a change in the destiny of a single individual can lead to a change in the destiny of a community, nation and ultimately humankind.” Reading the mission of the school—inspired by the premise of Sensei’s The Human Revolution—I realized that it was precisely what I wanted to say with my instrument and, more, what I wanted to say with my life. I accepted the position and stayed on there for 30 years.

I bet your mother was tickled by your career choice.

Everett: I’ll get to that. Suffice it to say I learned a lot over the course of my teaching career. I’ve taught many students who struggled to believe in themselves but who, with strong support, went on to realize their potential, some to receive wide acclaim. Early on, I found myself asking Why them and not me? But as I chanted earnestly for their happiness, those questions fell away. Working closely to understand each student’s strengths as well as where they had room to grow, watching them grow into capable, thoughtful, courageous people, I came to feel their successes as my own. Big and small, their successes became my greatest pride.

Where has this led you?

Everett: When the school’s founder retired, his successor set about expanding the school’s legacy. She wanted to expand, she told me, with a new school founded on the same mission. Would I consider being its principal? Actually, I was planning to retire. I’d long ago acquired ample finances to live comfortably. But I found I couldn’t say no. It was an opportunity, I realized, to once again step into my mission and help others do the same.

When did planning for the new school begin?

Everett: Around 2017. A yearslong project, it actually picked up speed during the pandemic. The planning meetings—with architects, city officials, donors, teachers and parents of prospective students—continued online. I took the calls from home, but not my home. I’d moved temporarily in 2020 to Washington, D.C., to be with my mother, 96 at the time and in the final days of her life. She watched me at work, in conversation, and asked me at the end of the day, “How do you feel about all this?” I could tell she had a hard time keeping her laughter to herself, probably thinking, Never say never.

What’s a day in the life?

Everett: My usual weekday? Now back in New York, I arrive between 7:30 and 8 in the morning, and usually stay on until 5 or 6. I greet the children in the morning and support the staff throughout the day. As an educational leader, I lead by example, learning as much as I can each day from the students, parents and teachers. I have a lot of contact with them. What I ask myself most often is How can I deepen my conviction in the mission of this school? and How can I support each teacher, parent and student in awakening to their own limitless potential?

I don’t know what the future holds, but I look around me now and see that I have become a person of true wealth, whose fortune continues growing, from and among connections with people.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles