Living Buddhism: At the heart of Buddhism is the spirit of a vow. Your journey to practice Buddhism is somewhat unusual, in that it began, in a way, with a vow—a promise to your father.

Sumedh Kaul: That’s true. I wasn’t yet Buddhist at the time, nor was anyone in my family, but we each made a vow, the same one, around the phone in my sister’s kitchen in Mumbai. We’d awoken to a call from my brother-in-law at the hospital, with the news that my father had died. A silence fell. And then my mother broke it, speaking with sudden resolve: “We each have to bloom,” she said, “like a flower so that he’ll be proud of who we become.”

Tell us about your dad.

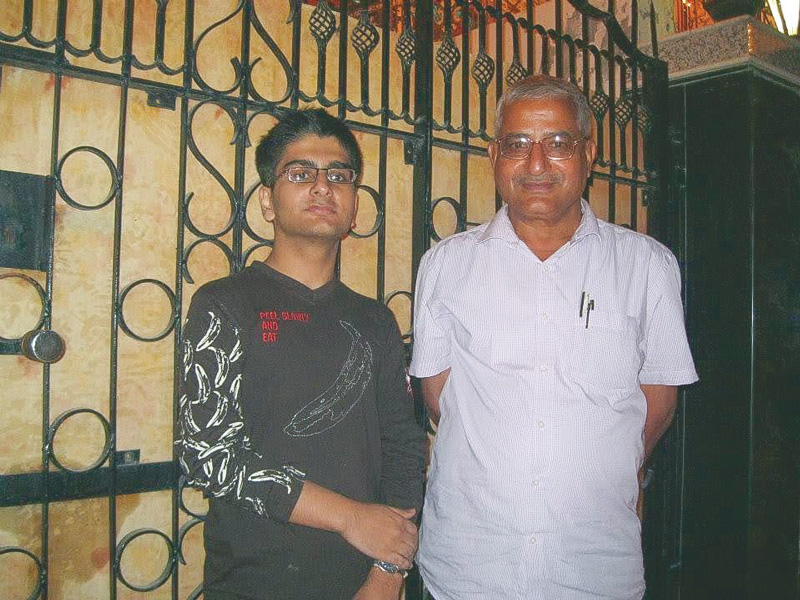

Sumedh: He was a dedicated man—to both his family and his work. Hard work, though, it often took him away to all corners of our home state of Punjab. An archaeologist, he ensured the safety and preservation of historic monuments and architecture. He had a home base in an office on the site of a magnificent tomb. When he was there, I’d go in the evenings, and he’d pour tea for the two of us, and we’d lose track of time. Or he’d call his friends out for a game of cricket.

Most often, he’d remind me to work hard—now in school and later in society. Hard work and a strict regimen, he stressed, were the keys to becoming a person worthy of respect.

He surprised us all when he retired at the age of 60. I was away, studying in neighboring Chandigarh when he did. It was there that I first heard he’d fallen sick with a bad case of Dengue—a mosquito-borne virus that wiped him out for weeks. He recovered but complained of stomach pain, which was diagnosed as pancreatic cancer. In the span of a week, my sister had flown him out to stay with her and her husband in Mumbai for its sophisticated medical care.

I was certain he’d rebound, but in September 2012, my sister called. “Come quickly,” she said, and I did. But by the time I had, my father had fallen into a coma. I’d expected to talk with him, to hear his voice one more time. And I hoped, until the day he died, that I’d get the chance. Still, I knew what he would have wanted to see me do. Returning from my sister’s in Mumbai, I redoubled my efforts in school, determined to live up to my father’s expectations, becoming a fine person through hard work and maximal effort. That determination kept me moving forward.

You’ve said that you counted your father among a very few close friends. Did you make new friends in Chandigarh?

Sumedh: I did. My neighbor and I met on our balconies, unclipping clothes from our lines. (Rarely will you find a dryer in India; wet clothes are what the sun is for.) He became my friend and began dropping by after work to talk. I’d make tea, and we’d lose track of time until his mother called, wondering where he was and whether he wanted his dinner cold. At some point, she came to expect the answer and began inviting me to join.

I’d had few experiences in friendship, and didn’t know what to expect, but somehow sensed that the depth of care, as natural as it felt, was a rare thing, too, even among neighbors.

This was the friend who introduced you to Buddhism.

Sumedh: That’s right. One day, I told him what I was challenging most: getting into a top dental internship. He told me that, when he had a challenge, he chanted Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, resolving to win. Scientifically minded, I could nonetheless grasp that my inner resolve could effect a change in my environment. So, we began to chant, just five minutes every morning, and then read a little something from Daisaku Ikeda. Others in the neighborhood were reading Daisaku Ikeda’s encouragement, he told me, and chanting the same Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. Usually, they gathered down the block at a discussion meeting, a five-minutes’ drive. I went and was impressed by the energy and the profound yet accessible principles up for discussion. Within three months,

I was accepted into a top dental program and had my first clear proof of the power of the practice.

Amazing! How did your internship go?

Sumedh: Terribly! I soon discovered that I was no good at clinical work. Frankly, I couldn’t help but wonder what my father would think, and whether the path I’d taken was in fact a dead end.

The program was in Mumbai, far from my friend in Chandigarh. I continued chanting, but never connected with the local SGI group in Mumbai. Chanting was all that kept me from throwing in the towel. And it was what gave me the courage, too, to change course.

Nearing graduation, I applied to a master’s program in biostatistics at New York University. I got in and, in the summer of 2018, moved to New Jersey, where I continued to chant, usually under my breath on the train between home and school. It wasn’t until January 2020, that I connected with SGI-USA members, meeting up for coffee in Jersey City. I sketched the outlines of my path in faith and asked if I could receive the Gohonzon. Surprised, smiling, they looked at me like, Where have you been? They connected me right away with my local district, and I received the Gohonzon in February 2020. Just in time—the following month, New Jersey went into lockdown.

You graduated in the pandemic—is that right? Was your plan to stay in the country?

Sumedh: It was, though there was no clear path to that outcome. Approaching graduation, I chanted fiercely to land work that offered a path to a visa. Daily, I read even just a page or two from the World Tribune or Living Buddhism, and it was this that fortified me for the rejections—one after the next—from every job I applied to.

Just after graduation, however, I could let out a breath of relief—I landed a project on COVID-19 at a community hospital in Florida. If I did well, I stood a chance of landing visa-sponsoring work when it was over. I put my head down and did what second Soka Gakkai President Josei Toda often admonished his disciples to do: “In faith, do the work of one; in your job, do the work of three” (see The New Human Revolution, vol. 22, p. 101).

The hospital asked me to do something that felt beyond my abilities: develop a resilient predictive model for COVID-19. Taken aback, I nonetheless said yes.

I worked late into the evenings, studying historic models tracking past outbreaks and making note of their findings and the reflections of the scientists who’d made them. Taking these into account, I began to draft my own model, chanting morning and evening to tap my creativity and overcome my deadlock. Upon completion, I was astonished to find that my model exhibited an impressive accuracy rate of 99%. Similarly impressed, the hospital’s CEO promptly disseminated it across various platforms, where it was put to use helping people make informed decisions on how to protect themselves and others from COVID. Consequently, the model garnered interest from scientists in South America and Europe, and I found myself presenting at a prestigious international conference.

As lockdown provisions loosened one by one and New York took its first breaths of normal life, I did too, feeling that I’d turned poison into medicine, proving myself for the first time in my chosen field. With this proof under my belt, I fired off a round of applications and received, in August, several guarantees of employment, one of them from a medical institution affiliated with Harvard University. I took it and began applying my biostatistics training to cancer research, something I felt my father would be proud to see me do.

As our SGI centers reopened, I was among the first to take on shifts for Soka Group and Gajokai, which are young men’s behind-the-scenes training groups. I was told by one of my young men’s leaders that I struck him as sincere, but also rather serious, somewhat business-like in my approach. It’s true that I considered Soka Group and Gajokai part of my regimen, a regimen I kept as seriously as a promise. For me, keeping my regimen was keeping my promise to my father. Looking back, as sincere as I was, I feel there was something missing from my practice.

And what was that?

Sumedh: At the time, I couldn’t say. But I found out the summer of 2023 when I was asked to attend a young men’s conference at the SGI-USA Florida Nature and Culture Center. Those who’d been warned it could be life-changing, but I just couldn’t bring my scientific mind to expect such a thing from a single weekend.

What did you find there?

Sumedh: First off, energy. Here, among 200 young men from across the country, there was an edge of joyful competition in the air, each person fighting for kosen-rufu with a deep sense of pride. It was thrilling. A feeling of: Let’s win together, whatever it takes. Let’s show the world with our lives the greatness of Buddhism! There was a part of me that felt reserved at first. But that changed with the keynote lecture, based on Ikeda Sensei’s in that month’s Living Buddhism. In it, Sensei discussed the shared vow of mentor and disciple to bring happiness to all people, and the energy unleashed when we base our lives on this vow. He states:

By cherishing a great vow, we build an expansive life state. By dedicating our lives to fulfill that great vow, we make the most of our limitless potential. By sharing that vow with others, we joyfully expand our circle of friendship, forge bonds of trust and cause our own and others’ dignity to shine.

Mr. Toda often said: “The greater our ideals, the greater our lives will become. No one becomes a true leader without hard work and effort.” …

Cherishing a grand vision and sparing no effort to achieve it, Soka youth are treasures; they will play a pivotal role in shaping humanity’s future. The world’s hopes for you are greater than ever. (April 2023 Living Buddhism, p. 60)

The concept of a vow was something I’d thought I’d understood, and in my own way, I had. But considering the young men around me, I grasped for the first time the source of their pride, which had little to do with achievements (though there were no shortage of these) and everything to do with who they were as people—people who showed with their lives the greatness of their mentor and in this way awakened others to the greatness of their own lives. This was what it meant, I realized, to be a truly great person. If I wanted to bloom, if I wanted to keep the vow I’d made to my dad, it was only natural that I put a vow for kosen-rufu at my core.

What did this do?

Sumedh: Lit a fire in my belly. Upon coming home, my faith was no longer part of a regimen but part of my soul. It was a fundamental shift. From here, everything changed. Every cause I made, every action I took, became a cause to do my human revolution, advance kosen-rufu and bring happiness to others. I began stepping out of my comfort zone, inviting every one of my friends to that summer’s young men’s outing. My approach to my practice shifted to: I don’t know how to make this happen, but whatever it takes, I’ll do it.

I began visiting as many of the young men as possible and wracking my brains for ways to inspire them and the friends I’d made to come out and make a connection with the SGI community. In the summer of 2023, my region brought out 48 youth for the young men’s meeting, eight of them my personal friends. The following year, we built on these connections, bringing out 96 youth to our chapter’s March Youth Peace Festival.

Many other young men in the chapter stood up with a fighting spirit to meet their friends where they were at, wherever that was—in the gym, on the badminton court, you name it.

Awesome. What about a personal goal—anything you fought toward in the March campaign?

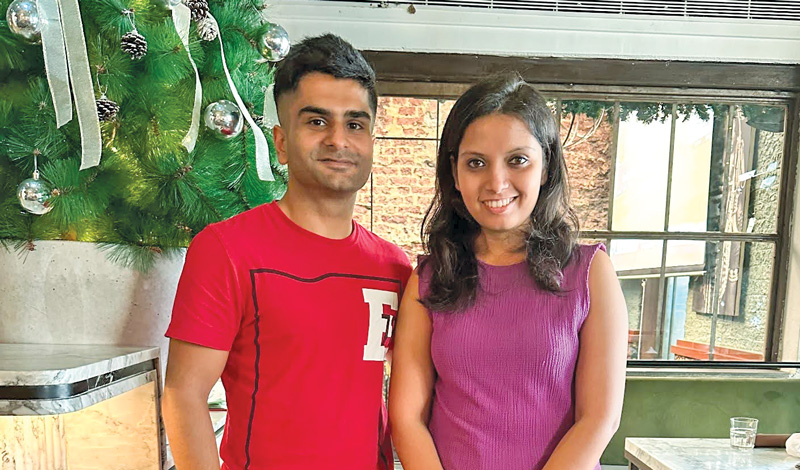

Sumedh: Yes, I did! Two big goals, in fact: 1) to propose to my girlfriend—she said yes!; and 2) to get my green card petition approved—it was in June!

Nice! What now?

Sumedh: As the newly appointed young men’s leader for North Zone, I’m determined to unite with friends in faith, to expand the ranks of our youth and bring my life to bloom to the fullest. I was a very shy person once, with few friends and a solitary regimen. Now, I have no qualms talking with anyone, have many friends who are always asking me to join them for daimoku, a talk, a badminton match. I keep a schedule, but not as a rule. I know if my father could see me now, he’d be deeply happy to see me doing the work that I do, contributing in honor of his life to the field of cancer research. But even more, I think he’d be proud, and even somewhat surprised, at the person I’ve become, the friend I’ve become to others, based on a vow for kosen-rufu.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles