by Ted Miller

Charlotte, N.C.

Every young person responds differently to trauma. Some turn it outward in anger. Others turn it inward on themselves. I, for one, went quiet.

At 12, I lost my older brother to brain cancer—a brutal thing that took him slowly, over the course of two years. I was still in shock when, at 13, my father died suddenly, overnight, of a heart virus.

I made no trouble, had no enemies, and for these very reasons was elected by my high school peers to homeroom rep, class president and student council, roles I accepted gratefully, wanting badly to do some good for my friends. But in these roles, I rarely spoke on their behalf. I hardly spoke at all. Fundamentally, I did not believe the world was within my power to improve.

This changed my senior year, when my buddy invited me to an SGI meeting. In those days, the message of grassroots movements was of opposition: antiwar, anti-authority, anti-this, anti-that. For good reasons, but not what I badly needed at the time. Arriving to my first discussion meeting, I understood immediately that I’d stepped foot into a peace movement, but one in a mood I hadn’t found elsewhere. These people—teachers, cellists, students, lawyers—were going places. And the message I got by being there was, You’re going places, too.

I received the Gohonzon and jumped in with both feet. When the opportunity arose to travel to Japan with SGI members from around the world, I saved up the airfare and went.

In the months leading up, I read a book about the Soka Gakkai’s founding president, Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, an educator far ahead of his time. Mr. Makiguchi’s thought led me to consider the proper aim of education, which boiled down to happiness.

In Tokyo, we toured the campus of Soka University of Japan (SUJ). In its main courtyard stood a bronze statue inscribed with an appeal to the students from the school’s founder, Ikeda Sensei. Later that day, while chanting, the words came back to me: “For what purpose should one cultivate wisdom? May you always ask yourself this question!” (The New Human Revolution, vol. 15, revised edition, p. 99). In an instant, it struck me. I’d be an educator and reformer, spreading the principles of Soka education.

In a little over a year of Buddhist practice, I’d sensed the exciting possibilities of life that 14 years of schooling hadn’t made me aware of. I came back to Michigan with a spring in my step, my college major decided.

Over the following years, I met and married my wife, Mary Lou, began teaching English at schools in Michigan, and received my master’s in English education.

In 1987, I applied for an English teaching position at SUJ and was hired on as the first full-time, non-Japanese instructor. As a newcomer to the school and the culture, I felt hesitant and unsure of myself. That changed later that year, when I met Sensei.

Thinking of my new students, I asked Sensei if there was a message I could convey to them. Without an instant’s hesitation, he responded, “Your growth is my message.” He went on: The teacher-student relationship is not different from the mentor-disciple relationship. If I wanted creative students, then I must plan creative lessons. If I wanted widely read students, then I must read widely. If I wanted avid learners, then I must be one. “Someday,” he told me, “I hope there will be students the world over who say, ‘I am who I am today because I studied under Dr. Miller.’” In ending, he said he expected that I’d play a historic role at SUJ.

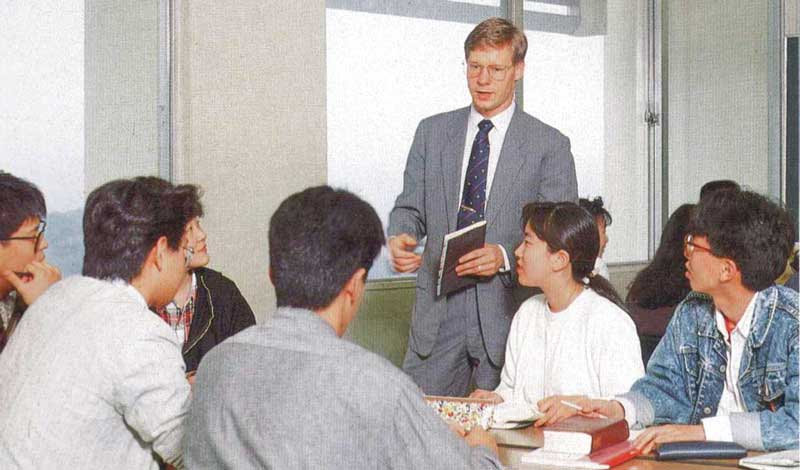

As you can imagine, that lit a fire in me. It gave me a vision of the kind of impact I could have. So, I shed my timidity and began to speak up. In Japan, English was being taught from podiums, in lecture halls, in Japanese. I proposed much smaller, more frequent classes, based on dialogue.

To my surprise, my suggestions were eagerly met, and over the course of my 14 years, these changes and more were made—what one administrator referred to laughingly as “the Miller Earthquake.” Sensei had shaken my timid self to the core, awakening me to my capacity to fight for reforms that would benefit our students.

In 2001, Mary Lou and I moved back to our hometown of Jackson, Michigan, and within a year I was working again, this time for a community college, teaching remedial classes for students considered not quite “college-ready.” A disturbing reality of these classes was the disproportionate number of students of color being placed into them, many of whom were dropping out. Many students, in fact, were not completing their college education.

I had found a new mission. I began to speak up, discussing the matter in earnest with my fellow teachers.

I discovered that my colleagues teaching remedial courses were aware of the issue but overwhelmed and operating alone. The general educators, however, were simply unaware, their focus trained on the students that made it into their classes, not the huge numbers dropping out before they made it there.

Initially most were of the opinion that the situation was beyond them to address. One by one, however, I found people wanting to make a fundamental shift: Instead of conceding that a student was simply not “college-ready,” we would become a college that was “student-ready.” The Buddhist concept of “many in body, one in mind” that I’d been putting to work for years in SGI leadership, could be put to work in this endeavor.

It took nearly a decade, but as a core of like-minded people, we made ourselves heard and expanded our ranks. We began to organize across departments, directing resources to promising initiatives and tracking outcomes. As certain ideas were applied and proven, others threw in their weight, our strength and creativity growing exponentially.

In 2014, my provost asked me to co-chair the total redesign of our college system. We launched it in 2016 and by 2018 had doubled and tripled key student success measures while halving achievement gaps. Our college became known as a hotbed of innovation and model of student success initiatives.

Today again, I cast aside my provisional identity—Ted the Timid—and reveal again my true identity: Ted the Fighter, the changemaker, the Ted my mentor introduced me to. With my growth, with my voice, through my actions, I will relay Sensei’s undying message to young people: “I have my mission, which is mine alone. You too have mission, which only you can fulfill” (The Sun of Youth, p. 6).

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles